Studio Context

Our studio brief was to imagine a world without cars. Under this theoretical umbrella, we were to explore the topic of segregation. The subject of urban segregation is complex and difficult to parse. The first thing that comes to mind for many is social issues; segregation that cuts along racial and economic lines, for example. But typologies of segregation also run along physical lines. No matter which typology you pursue though, segregation is always a matter of forced separation. In the urban context, elements like highways that physically divide communities are an obvious culprit. Perhaps less obviously, but potentially more interesting, are typologies of the architectural fabric itself. It is easy to see how much segregation has accumulated in the urban fabric of cities due to the allure of private automobiles. How might we do away with this segregation? How might cities be redesigned if they didn’t have to cater to cars? What would happen to the monolithic infrastructure which segregates people and degrades the pedestrian experience?

Cities the world over are home to industrial neighborhoods. Once economic powerhouses of heavy industry at the outskirts of town, many now languish as they are absorbed into ever-expanding urban landscapes. And as post-industrial cities have grown up around their heavy industrial infrastructure, once proud blue-collar industrial neighborhoods struggle with their identity and place in the modern world. Impenetrable and monolithic blocks act as an architectural tissue of segregation between and inside urban communities. These spaces may be ripe for intervention, but can they be reimagined without sacrificing the heritage and civic pride which has been the foundation of their communities for generations? How might these communities rejuvenate the urban fabric with new connectivity, and breathe life back into deteriorating industrial neighborhoods? Can it be done all while avoiding displacement and gentrification? These questions and more are the basis of this studio project; away with cars, and away with segregation.

Case Study Area

Barcelona’s El Bon Pastor neighborhood is a unique case study that we discovered after a demographic mapping analysis of the city. When we mapped age, ethnicity, income, density, and property price, the neighborhood stood out as an area where the mapped values clashed. With further research and multiple site visits, we decided that as a case study, it fit the studio brief for multiple reasons. The residential town center is surrounded by a sea of industrial land which segregates it from neighbors to the North, West, and South. That industrial land is home to a major concentration of automotive businesses; dealerships, manufacturers, mechanics, storage lots, and so on. What happens to these businesses in a world without cars?

Cultural Context

There is another typology of segregation occurring in El Bon Pastor as well. The history of the neighborhood becomes important here. The town started out as cheap workforce housing for nearby industrial estates. The main housing complex, known as the casas baratas, became a hub of cultural identity and community for the industrial blue-collar locals. Poor working conditions and political oppression from dictatorial governments forged a neighborhood identity with a strong, independent community feeling and a penchant towards political activism. That identity is tightly linked to the casas baratas.

In recent years, the city of Barcelona has been on a mission to replace the original housing stock, which has long outlasted its intended lifespan. In doing so, most of the casas baratas have been torn down to make way for new, affordable housing blocks. Although the city claims to have made an effort to avoid displacing longtime residents, lack of local access to the planning process has rekindled old fires of political oppression. Locals are fighting to defend a way of life and a culture that is at risk of becoming a memory. We feel this is all central to our case study analysis of segregation. It’s more subtle than the freeway which segregates the town from the adjacent river, but it is nonetheless a form of segregation that is occurring over time on a cultural level.

There are many projects underway that intend to modernize the neighborhood. A 4km long park being built over the high-speed rail to the west will help to connect El Bon Pastor to its neighbors in Sant Andreu. New amenities will be built in the areas around the park as construction progresses. The giant, defunct Mercedes manufacturing plant in the center of town will be redeveloped into a mixed-use hub, home to a new university and technology park, housing, and public space. But these redevelopment efforts have no shortage of local critics. The conversation around gentrification is front and center, and the track record of poor alignment between locals and the municipality is creating distrust failing to engender local ownership and identity.

For us, the challenge was to explore an intervention that could simultaneously melt away the segregation caused by the languishing automotive industrial fabric, while also building a sense of local ownership and identity by bridging the gap between the future and the cultural past of El Bon Pastor.

Theory

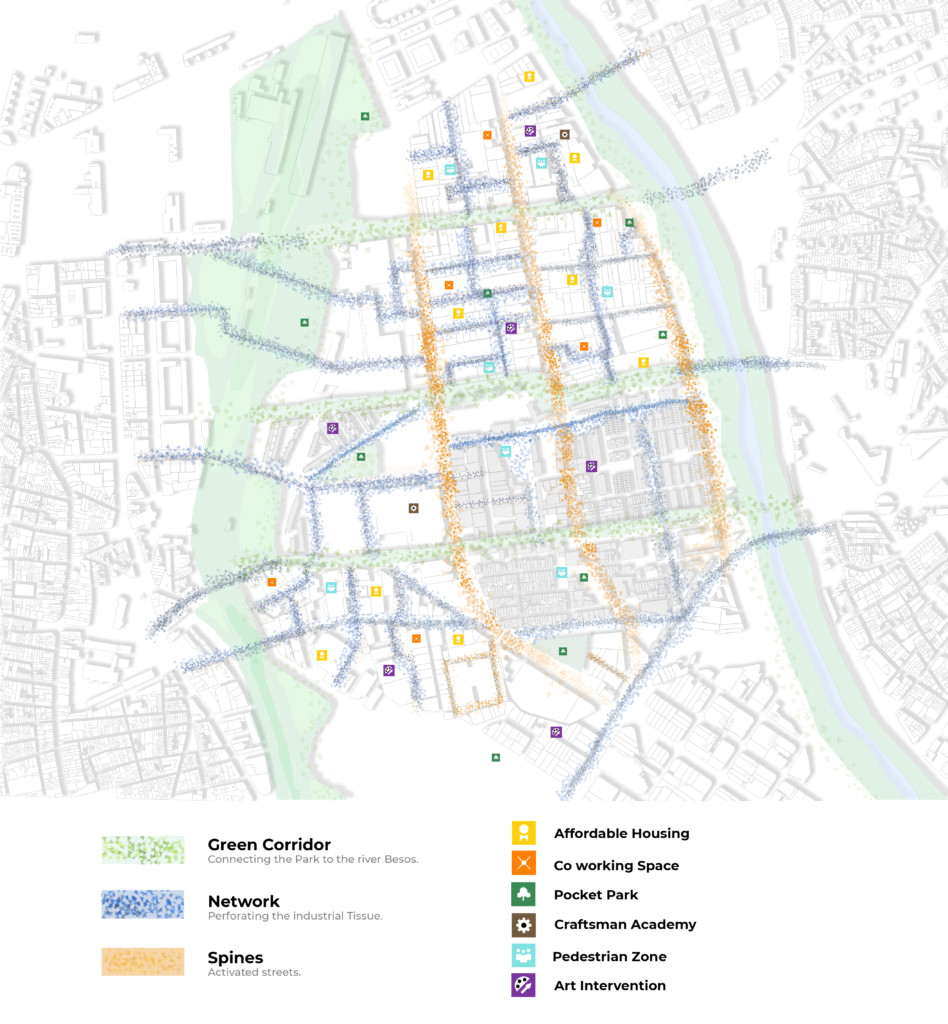

No matter the form segregation takes, integration and connection are the antidotes. The following is an adaptive reuse intervention that operates cyclically to generate integration and connection over time. We designed a theoretical framework to create integration and connection in the disconnected and monolithic industrial tissue found in El Bon Pastor. In our design work, we focussed on the small scale and the near term in order to constrain our thesis to the realm of the possible, but ultimately the objective is to catalyze long-term, high integrity change in the urban fabric.

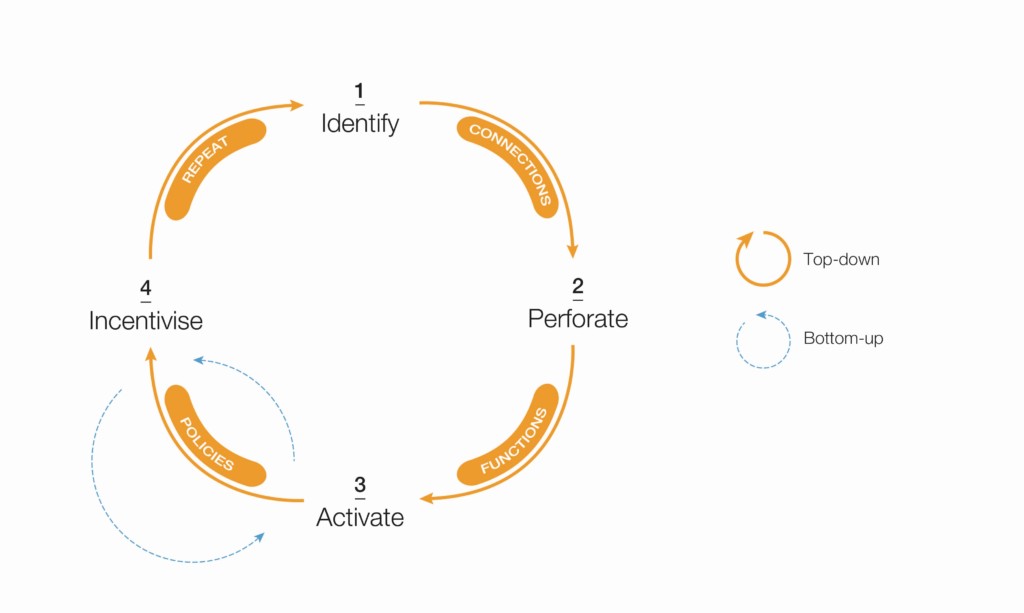

The clockwise orange cycle is a top-down process that occurs once for every new connection that is created. The blue counterclockwise cycle is an ongoing, spontaneous cycle that is driven by community actors over time.

The cycle is based on a four-step methodology:

- Identify where a connection is most needed based on poles of attraction in the urban context, and most feasible based on existing unbuilt spaces within the industrial fabric

- Perforate the physical structures at the points identified in step 1 to create a new linear connection through the existing buildings and barriers

- Activate the new linear connection by adding functionality with tactical urbanism and building out new mixed-use spaces in the adjacent buildings

- Incentivize the local community to take ownership over a bottom up cycle of ongoing activation with a goal-oriented policy framework

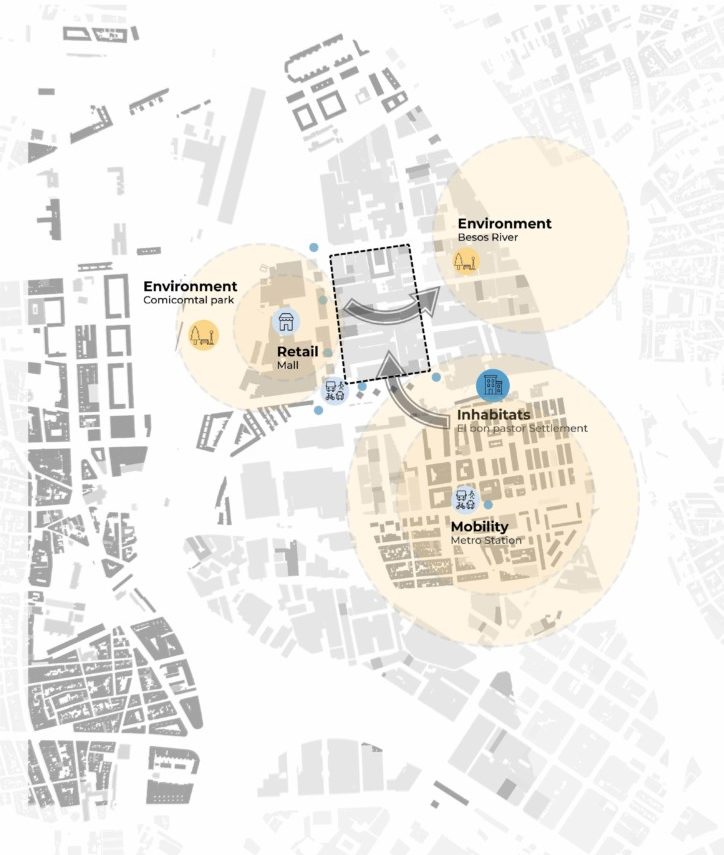

Let’s look at how the adaptive reuse cycle can be applied in the context of the El Bon Pastor case study. First, we analyze the urban context around the industrial area to identify poles of attraction. We selected the highlighted block as our area of focus because it is at the epicenter of multiple poles of attraction such as the residential core, the mall, and the river. Moreover, it is representative of the monolithic, impenetrable industrial blocks which our intervention aims to address.

Next, within the selected block, we look at all the existing unbuilt spaces. By analyzing where unbuilt spaces interface with poles of attraction, we can develop a roadmap for the prioritized sequence of perforation over the course of multiple turns of the cycle.

The plan of connections above shows which buildings are acting as barriers to the new connections. Each of these buildings should be perforated following a principle of minimal necessary demolition. The resulting space created after one cycle will then be activated based on the typology afforded by the width and character of the perforation. After many cycles a new network of connections emerges:

Each new connective space that is created with a perforation of the industrial tissue must be activated in order to draw users in and through. Passages through monolithic or unwelcoming architecture only perform in accordance with how safe, comfortable and functional they feel to users. Function follows form in this case as the activation of each space will be a function of its physical typology.

We believe it is not enough to initially activate the new spaces. The final stage in the cycle is to incentivize the local community to participating in an ongoing cycle of increasing activation. If the local community doesn’t take ownership over the ongoing development of the spaces, the intervention would be considered a failure. The possibilities for activation are endless, but in this case study we suggest the following principles:

- Community engagement

- Affordable housing

- Job creation

- Cultural preservation

- Public space

- Brownfield reduction

With these 6 principles as guides for policymaking and creative incentives for community actors, the connective spaces will breathe new life into the industrial area.

Arcade typology activation

Alleyway typology activation

Over time, as new connections are identified, perforated, and activated, a whole new network emerges across the neighborhood. The area becomes well connected and walkable. Watch as the segregation of industrial tissue melts away with each set of new connections in the Space Syntax analysis below.

New affordable housing, entrepreneurial ventures, services, amenities, and community spaces bring activity into the industrial fabric, slowly reactivating the area and generating economic growth. As a case study, El Bon Pastor provided the studio team with fertile ground for this type of theoretical intervention. But we believe that the model could work in any context where industrial areas are causing segregation in the urban fabric. Identifying where connections are most needed, perforating the architecture with linear connections, and activating those connections by incentivizing local residents and organizations to engage with the new spaces. It is a process that is location agnostic, as long as the principles and policies involved in incentivizing community engagement address specific local issues and speak intimately to the local context.

We have a long way to go before our cities will be free from the burden of designing for cars, but we must pursue the agenda. The data are in; fewer cars and more spaces designed for people means a higher quality of life, better health, and stronger local economies. There are many dimensions of redesigning cities for people, and this project explores just one aspect of one topic. There are many others to explore, and a lot of work left to do.

A vision for El Bon Pastor- a connected and productive neighborhood built between two large natural areas. A place where a strong industrial past creates a dynamic future without displacing long-time residents or destroying the cultural heritage.

‘Industrial Reconnection’ is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed in the Master in City & Technology 2021/22 by Students: Weronika Sojka, Pushkar Runwal, and Ocean Jangda; Faculty: Eduardo Rico, Mathilde Marengo, and Iacopo Neri