The fear of technology, particularly communicative technologies, almost always caused fear and controversy at their onset: telephones as intrusive in the 1800s, radio as a distractor to reading, television as an obstruction to human interaction… [Daniele]. The world continues to witness these doubts with every modification to whatever people are used to. The norm was very much ‘threatened,’ yet again, during the pandemic, and the interpretations of governance and the repercussions of the pandemic were controversial at that. The vulnerability of the ‘norm’ was proved yet again in the post-pandemic city, and its respective governance. How does the post-pandemic city instrumentalize technocratic governance?

QR Code Access to Respective Presentation

Contrary to popular belief, that post-pandemic technology and governance can only be autocratic/ dictatorial [Bratton 54], Covid-19 has morphed governance into a real-time liberated data transfer practice: amongst others, there is a liberty of movement in the city, fingerprints as means of access, optics and eye-scanning as means of identification, and QR code scanning as means to decentralize access to information. [“Mobile Location Data and Covid-19: Q&A”].

The post-pandemic city was characterized by the evacuation of public spaces, civic and commercial centers, and educational and governmental institutions [Bratton, 54]. The city witnessed the transformation of amenities that were once known as places in the city into applications and appliances in the domestic, platform delivery services included. System administrators and couriers kept the world moving when the government was not necessarily able to. Remote education and labor, arguably deemed impossible before Covid-19, became the most practical option for many. The pandemic has reminded us that the ‘planetary’ precedes the division of societies and states: the epidemiological view of society surfaced the notions of biological interconnectedness. Having said so, many organizations digitized their works and focused on what’s necessary. This phenomenon extended to governments and state services which have shifted from practice to information and tracking. Big data governance and information tracking of the planet’s populations becomes prevalent [“Mobile Location Data and Covid-19: Q&A”]. Relating the planetary to governance has bred ‘Biopolitics.’

Biopolitics is a fusion between politics and human biology, a term coined by Foucault, in which he describes it as rationale and/ or political tool which sets the administration of life and population as the noble goal by ensuring, sustaining, and multiplying life in ways that put life itself in order [“Biopolitics & State Regulation of Human Life”]. Foucault argues that biological existence is reflected in political existence. The interconnectedness that vast populations have been getting in touch with resonate in Biopower and Bioregionalism, facets of Biopolitics. Biopower wants to regulate populations and understand the human as a resource whose knowledge is to be retrieved for the sake of comprehension and the development of mapping human endeavors [“Biopower”]. Connecting this political rationale to the territory suggest that ‘bioregions’ will ensure just and sustainable political, economic, and cultural frameworks [“Bioregionalism: The Need for a Firmer Theoretical Foundation”].

Because of these rationales, governance has become opportune, and has witnessed a shift from ‘Perspectivistic’ to Distributive governance. A panopticon, invented by Jeremy Bentham in the 1700’s [“The Panopticon”], is a disciplinary practice used in detention centers that uses a central observation tower to monitor the prisoner’s cells around it. The observation tower is designed in a way that prevents the prisoner to see inside it, and the guards inside to see out [Brown Edu]. The term ‘panopticon’ was later quoted and developed by Michel Foucault in the 1970’s when he related it to our modern everyday life and describes it as a symbol of social control. He argues that citizens in modern society developed an internalized authority which is expressed in societal norms [McMullan Thomas].

We as a society often feel obligated to respect laws or norms even if there isn’t an actual guard observing us. Just like a panopticon, people never know if they are being watched so they always act like they are most of the time. The “Digital Panopticon,” on the other hand, is a control developed by the technologies that surround us. The control this time is voluntary and no longer in isolation as the user becomes an asset of the monitoring system. The digital environment is characterized by the devices and data exchange which was once tamed, and now taming populations.

‘Perspectivistic’ Panopticon: Observation Tower Accesses the Sight of Cells from the Center

Distributive ‘Panopticon’: The “Digital Panopticon”

In relevance, the actors of the post-pandemic city are tracking technologies, post-pandemic governance, and the city itself. The ripple of this triangular relationship can be deciphered on the urban, neighborhood, and individual scales. Tracking technologies manifest differently between cells towers, barcodes, and several forms of QR scans. On the urban scale, the technology of cell tower triangulation was used in governance to monitor and control the expansion of the pandemic which has given the state real time access to the person, neighborhood, and city.

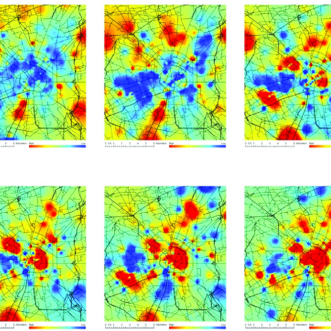

This ‘increased’ surveillance has taken shape in the urban fabric by creating a multi-scalar programming: our physical city has become a space for machines and communication and tracking services which affected our understanding of streets and necessary programs. The collection of aggregated data took place in Milan using this technology [“Mobile Landscapes”]. In “Mobile Landscapes,” the said distributive technocracy is further emphasized in the graphic manifestations of the density of urban activities and their morphology through space and time.

Cell phone call density in Metropolitan Milan between 9 am and 1 pm, “Mobile Landscapes”

QR code scanning is a tracking technology that connects the urban to the neighborhood, and consequentially, the individual. QR code scanning varies in size and impact. On the individual scale, populations connect to themselves and the larger data infrastructure around them by scanning social media addresses, business cards and resumes, transportation tickets, shopping, and even codes on cemetery blocks. On the neighborhood scale, QR codes are scanned form metro billboards, stands in local markets, reception spaces, aerial codes made by trees, and drone-illuminated codes.

In Lebanon, citizens were not allowed to exit their homes before filling a form that identified their destination and deadline to be back home. These tiny codes redefined the relationship between citizen and state [“Moph”].

A QR Code in Lebanon That Validates the Carrier’s Health

To achieve a productive symbiosis between governance, city, and tracking technologies, Germany decided to heavily include medical bodies in governance and decision making: Merkel managed to develop political protocols and economic models based on verdicts from medical centers [“Populist, Technocratic, and Authoritarian Responses to Covid-19”]. From here, a question poses itself: are we heading to a monochrome reality of technocracy where the governors and political actors are physicians and medical practitioners/ bodies themselves? If so, for how long?

On another note, tracking technologies and big data governance today assumes that each person carries one device. This cannot be true particularly in the case of Sierra Leone where devices are shared and traded [“Mobile Location Data and Covid-19: Q&A”]. Places of conflict with damaged or low signal, target zones with manipulated connection, and areas of natural disasters are also less likely to benefit from the technologies that first world governance are taking advantage in Biopolitics today. How does big data governance and tracking technology support vulnerable places and areas of natural disasters? How can tracking technologies defeat the assumption that each person carries on device? Could tracking technologies be inadequate to support the novel agenda in technocracy towards sustainable bioregions?

List of References [MLA Format]

- Bratton, Benjamin. The Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World. Verso, 2021.

- Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World. VERSO BOOKS, 2022. Demetri Kofinas, DK. (Host). (2021, July 05). Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World | Benjamin Bratton (No. 197). [Audio podcast episode].

- “Biopolitics & State Regulation of Human Life.” Oxford Bibliography, 2016, oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0170.xml.

- M Foucault The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality Volume 1 (1976) (trans. R Hurley, 1998).

- Bratton, Benjamin. “18 Lessons of Quarantine Urbanism.” Strelka Mag, 22 Dec. 2020, strelkamag.com/en/article/18-lessons-from-quarantine-urbanism.

- Danielle, Taylor. “9 Times in History When Everyone Freaked Out About New Technology.” Ranker, www.ranker.com/list/historical-freak-outs-about-new-technology/taeyura. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

- “Biopower.” Oxford Reference, 2010, oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095507415.

- “Biopolitics & State Regulation of Human Life.” Oxford Bibliography, 2016, oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0170.xml.

- “Bioregionalism: The Need For a Firmer Theoretical Foundation. Archived 2018-11-05 at the Wayback Machine“, Don Alexander, Trumpeter v13.3, 1996.

- “Internalized Authority and the Prison of the Mind: Bentham and Foucault’s Panopticon.” Brown Edu, 2009, brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/13things/7121.html.

- McMullan, Thomas. “What Does the Panopticon Mean in the Age of Digital Surveillance?” The Guardian, 21 Feb. 2017, theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/23/panopticon-digital-surveillance-jeremy-bentham.

- Home Page. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from

https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/0/22862/moph-mobile-application-.

- “Mobile Location Data and Covid-19: Q&A.” Human Rights Watch, 28 Oct. 2020, www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/13/mobile-location-data-and-covid-19-qa

- Populist, Technocratic, and Authoritarian Responses to Covid-19. Items.

https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/democracy-and-pandemics/populist-technocratic-and-authoritarian-responses-to-covid-1/

- “The Panopticon.” Bentham Project, 9 Apr. 2019, www.ucl.ac.uk/bentham-project/who-was-jeremy-bentham/panopticon.

Urban Tracking Technologies: Post-pandemic City & Governance is a project of IAAC, the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, developed during the Master in Advanced Architecture (MAA01) 2020/21 by students: Nader Akoum, Rahma Hassan, and Yervant Megurditchian; faculty: Manuel Gausa, Jordi Vivaldi.