INTRO

Presence of difference or division is a key entity in the creation of a system and the class system is no exception. There is no doubt that the class division has been present from time immemorial but the societal hierarchy and exploitation of human resources has caused massive fractures in the social fabric, giving rise to a growing divide and placing an overwhelming economic burden onto future generations. Unequal distribution of wealth and power have deepened the divide and its expression is quite evident in the housing market and economic system. The capital distribution is skewed and the lack of affordable housing is causing generations to remain in an eternal credit system. Ben Tippet’s Split, Class Divides Uncovered, provides a lens into the class division from various angles and is a reminder that class system is not an issue of the past. As Tippet claims,

“To bring us out of the current crisis and on the road to individual and collective success we need an organized, inclusive working class movement to take on the power of the wealthy elite.” (Tippet 2020, 11).

This essay will argue that the model of the cooperative, backed up by the advanced technologies, has the potential to bring individuals from different race, gender, tribe, class, economic means and cultural diversity to cohesively strive towards a sustainable form of living by mending the class divide.

Cleveland, Frederick “Popular Control of Government.” JSTOR, (2019.)

HISTORICAL TRAJECTORY

People have, since the first homo sapiens, lived in community first and foremost as a way of survival (Smith 2018, 21). Communal living enabled the division of labour, creating a system where everyone relies on one another for survival, which in turn strengthened the likelihood of long-term survival against foreign invasions. Though contemporary society functions on a similar basis whereby one relies on another, albeit indirectly, the advent of globalization as well as the increasing wealth across a global scale has created a de-communalized reality (Smith 2018, 21). In the modern age where the majority of the global population lives in or in close proximity to cities, humans no longer need to cultivate the land or hunt in order to survive (68% of the World Population, 2018). More so than ever before, people have learnt to live independently, isolated from the very source of their own survival, the land, leading lives whereby classes do not interact, reinforcing and intensifying the hidden class divide that is so entwined into our everyday lives. In order to understand how the built realm plays a role in the class divide, we need to look back to the turning point whereby people stopped using the land for themselves.

“Enclosure,” Wikipedia (Wikimedia Foundation, November 3, 2021)

As Tippet claims, the enclosure of the public lands is arguably the origin of the modern day segregation present in housing between the classes today (Tippet 2020, 45). Established originally by the feudal lords in 15th century England, the act soon began being implemented across a global scale (Tippet 2020, 45). Living off the land essentially became impossible if you did not own it, and yet, ironically those that owned the land never worked on it themselves. Rather, they left the intensive physical labour to the peasants in exchange for a wage (Tippet 2020, 45). Where once living off the land was crucial for survival, by enclosing the land and paying individuals to manage it, those who owned the land essentially deprived the majority of the population from using the land for survival, something which has raised countless legal and moral questions, such as who is to say who truly has access to land. This act continues to form the fabric of the contemporary housing issue and today, the controversial privatization of public lands continues to affect people across a range of wealth classes.

A modern day cooperative operates under similar principles of those before the enclosure of public lands. Where peasants made use of the land for food, shelter, and water, and worked together to divide the labour, modern day cooperatives aim to achieve the same goal.

STATE OF THE ART

LA BORDA

Being a young person attempting to ‘make it’ in this world, one of the most daunting challenges that lies ahead is having the financial means to be able to buy a future home. However, the odds that anyone in this generation will become homeowners are becoming slim to none. After the global housing market crashed in 2008, real estate prices have only continued to rise (Gracia 2018). Leading to now, having our generation called ‘Generation Rent’ as Tippet states,

“If things carry on as they are, our generation will on average remain trapped in the extortionate private rental market throughout our lifetime” (Tippet 2020, 90).

How do we escape what seems to be inevitable? For the people of Sants, Barcelona, they became resilient of this perpetuating future in 2012, protesting for their right to not be evicted from their homes. Out of this protest a group of 15 people emerged to form a cooperative housing solution, thus, the idea of La Borda was born (Housing To Building a Community, 2020).

Two years before the concept could be brought to fruition, the Barcelona City Council approved in 2014 that the public building, Can Batllo, would become the framework for La Borda. After the approval to use this public building the group of 15 tripled in size and the members became the future residents of La Borda. Those members not only were the residents of La Borda, but also the directors of the space, acting doubly as the construction workers for their own home as well as the managers, ensuring that their social housing will prosper. (Lacol 2021) The key ideology that assures the success of La Borda is its adaptability. Understanding that members will come and go, the building in its modular nature lends itself to being able to morph into whatever configuration the new users need (Lacol 2020).

Even though speculatively La Borda seems to be the answer to solving the housing crisis, it still divides the poverty line. La Borda claims to be geared towards the lower class as it does not allow people who make above a certain income to become residents, however, in order to join the community you must contribute € 18,500 to the shared capital (Housing To Building a Community, 2020). Though this amount will be returned to you if you leave, most people that are considered low income or are in poverty do not have this amount of money in savings to be readily able to join La Borda. Making it so that there is only a select bracket of people that are actually able to join. For the class of people that can afford to join La Borda, but can’t afford to buy a home this is the perfect alternative, but there is no escaping some type of class divide. La Borda illustrates what can happen in the philosophy of a cooperative and does help to mend the gap for those that can join, however it is still missing the mark in being applicable for everyone.

Iolanda Bianchi, Can Batllo, (2011.)

PONTE TOWER

“Ponte starts off by being a tower, a round Tower… and the whole outside is made out of raw concrete, unpainted, unpolished… as soon as it was built it was voted South African second ugliest building [not even honoured by the first place].” – Rodney Grosskopff (Mars 2017).

Under its dystopian appearance, Johannesburg’s Ponte Tower is a large-scale laboratory for the city, where a constant version of the city seems to emerge. In 1960, the Apartheid or “policy of good neighbourliness” as Hendrick Fulfut (or architect of Apartheid) describes it, was in place for already ten years. This policy not only prohibited interracial exchange but was designed to implement a cheap “black labour”. The black community of South Africa (SA) received a lower-grade education in comparison to the white community while simultaneously being pushed to work from a young age. As a result, the South African economy underwent exponential growth and subsequently their currency, the Rand, surpassed the value of the American Dollar. The increase of cheap labour by the authorities and the demise of the quality of education to the black community lead to the downfall of skilled labour in SA. The government then initiated a debauchery campaign of skilled “white-men” workers coming from Europe, which later extended to all parts of the world, and as a result the city of Johannesburg saw its population rise by fifty percent from 1963 to 1972 (Mars 2017).

During this time, no people of colour lived in the city center of Johannesburg. They were only permitted to circulate to work and subsequently return home to townships situated outside the boundaries of the city, by 9 pm. The area of Ponte, prior to the construction of the tower, was established as the poche neighborhood for European immigration. The luxury Tower, at the time of its completion in 1973, represented SA’s economic accomplishment, and stood as a symbol of white dominance.

Soon after the Ponte city tower was fully accomplished and its habitants settled, it was described as the first “grey” area in Johannesburg, as it was not uncommon to find an Italian occupant walking the corridors with his coloured wife. The division between ethnicities was blurred as the official enforcement could not be conducted within the tower. The tower saw a sudden increase of black families moving in, which was reciprocated by the raising of the rent by the government in the hope to dissuade new black families to move in. This had the opposite effect as families found the way to sublet and repartition the existing flats to welcome more families. Furthermore the white habitants found a tendency to move out of the cities into residential suburbs. The Ponte City Tower then found a new function than a simple housing tower, it was seen as a gateway from the Townships or other African countries into the city. In the film documentary, Africa Shafted, by Ingrid Martens, a series of interviews take place in the elevators of the Tower where local habitants confess their experiences. Most perceive the Tower as a safe haven, welcoming all foreigners in a place which, ironically, was designed to segregate them (Martens 2011).

The Ponte City Tower was built in a time where the apartheid was regnant, and the wealth, race, and cultural gap was prominent, reinforcing the divide amongst the communities. The case of the Ponte Tower remains as just an example among many representing the severity of the apartheid. Despite the Tower being originally built to exclude a certain population, the tower now represents a base for a society in need, as most of its inhabitants immigrated from neighboring countries in the hope to find work and a more suitable life. Today, the Tower is described as an insalubrious, dangerous space, deprived of local government funding, and remains a place where the white community are unwelcome, reinforcing the division between the white and the black communities.

Ryan Lenora Brown, “Ponte Tower” ( 2017.)

B-MINCOME

In the fourth chapter Money, Who Wants to be a Billionaire? Tippet discusses the current method of distributing money fairly, which consists of redistributing the wealth of billionaires through taxation, politics, and charitable giving. In an attempt to investigate how this method of operation could be changed moving forward, cooperatives and real utopia models were researched and analysed. Utopias of a classless society, without markers or a coercive state, are organized around the principle of “to each according to need, from each according to ability” (Wright 2011, 37). An example of a real Utopia that operates around this principle is the Universal Basic Income (UBI) model. UBI is unlike the existing government services that aim to close the wealth gap. Most existing programs provide services such as education and healthcare as well as additional income transfers including general welfare, family allowances, and tax deductions (Wright 2011, 41). Following this notion, Ben Tippet states “Let the billionaires create the wealth first and once they have done their magic, we can use politics, taxation and charitable giving to make sure that this wealth is redistributed to those who have lost out.” (Tippet 2020, 58).

In the case of UBI, services such as education and healthcare would still remain but the income transfers and government subsidies would be eliminated and in a way, be replaced by the UBI. By eliminating the additional income transfers, the cost increase associated with the UBI would be quite small in welfare systems that currently provide income support (Wright 2011, 41). To test this theory, a study called “An experiment to inform Universal Basic Income” was conducted based on reviewing the statistics of a two-year experiment in Finland. The study concluded that people benefiting from the basic income were marginally more likely to be employed than those who were not receiving the grant (Allas et al. 2021). In addition, the average life satisfaction of those receiving the basic income was significantly higher than those who were not. This can be attributed to the fact that those receiving the income reported better overall health and lower levels of stress, depression, sadness, and loneliness (Allas et al. 2021). The initial experiment in Finland had inspired other cities and countries to test these theories for themselves, including the city of Barcelona.

B-MINCOME is a pilot project being carried out over a two year period, in 1000 households randomly selected from three of the poorest districts in Barcelona (Coelho 2019, par. 1). The economic aid of B-MINCOME complements the income of project participants to test if the increase of income will improve the quality of life, increase freedom, and most importantly reduce the dependence on public subsidies. (Laín, 14). The UBI model operates as a real utopia, concretely demonstrating the principle of “to each according to need, from each according to ability” (Wright 2011, 37). UBI flips this existing method on its head by providing support to those who need it, when they need it, instead of redistributing money after the fact. This example of a successful cooperative supports the idea that cooperatives could contribute to mending the gap because

“The class system, even with its most respectable face on, is one where the wealth of the richest man relies on a system that keeps the poor in place” (Tippet 2020, 57).

Cañizares, María Jesús. “La Mina Vuelve a La Peor Época De Los 80.” Crónica Global. Crónica Global, ( 2019.)

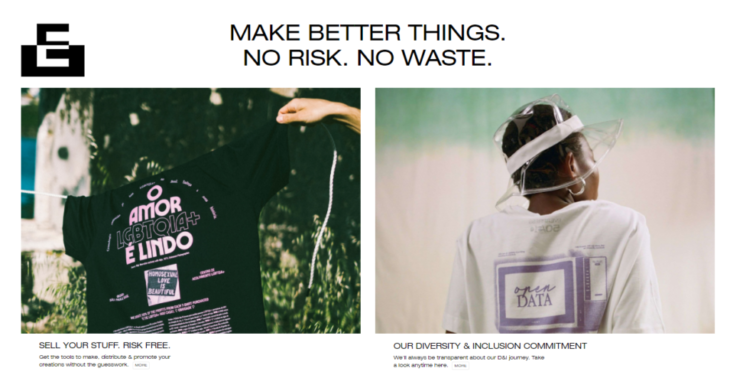

EVERPRESS

In contemporary society, the mass production of clothing results in excessive consumption of water and primary resources. In an effort to reduce the waste throughout the production process, the clothing company Everpress which is an example of an online cooperative, operates through a bidding system, whereby a minimum number of buyers are needed before the clothes are sent into production. The brand, functioning in a comparable way to a cooperative, allows designers all around the world to propose their own unique design for various items of clothing, which are then sold on the basis of a bidding system through their online platform. This responsive system allows Everpress to print and send the exact amount of clothes for production, limiting the material waste. Everpress represents more than just a brand acting in its era. Not only does it promote a minimal way of production, offering a responsive solution to the current environmental and social circumstances, but it also allows for young designers to propose their own unique designs in exchange for a wage. The platform therefore fosters the promotion of designers and creates opportunities for collaboration across a number of brands at a number of scales.

Despite the brand’s environmentally-friendly framework, the scale of Everpress’s production remains limited by its infrastructure. Nevertheless, Everpress provides a framework for responsive design that has the potential to foster meaningful change over a long-term period.

Everpress.com

CASE STUDY

FARMHOUSE, PRECHT ARCHITECTS

The Farmhouse, a project by Fei and Chris Pretch, is a design for a cooperative operating under the main goal of combining food production and city living. It’s design not only accommodates living spaces, but also actively and cooperatively uses the open spaces for farming aspects and even houses a supermarket at the ground level that will sell the produce of the vertical farm to the public, and so the project is simultaneously private yet communal (Block 2019). Because of its wood-based structural system, the modular design is adaptable to any given site as it can be prefabricated off-site, allowing for flexibility in its size and division of spaces which can be rearranged to fit its needs. With the abundance of plant growth present across the entire structure, the building inadvertently reuses and recycles water while simultaneously cleaning the city air of carbon dioxide pollution, creating healthier living conditions. This, in combination with its wood-frame timber structure, the production of which creates less pollution during the construction process than steel or concrete, aims to reduce the structure’s carbon footprint while improving the quality of life within the city (Baldwin 2019).

The Farmhouse’s design also creates an opportunity for social cooperatives. For people to move into the building and take full advantage of its resources, they would need to make connections with their neighbors and find out how to keep a sustainable garden. The occupants therefore connect through a common objective that is non-profit based. It further creates an opportunity to attract a diverse population from different backgrounds and economic standings to inhabit the building. The staff of the building (those managing the supermarket and the communal gardens, the cleaning staff etc.) can also live in this building. In conclusion, the building provides a successful framework for a self-sufficient community, moving one step closer to mending the gap between classes. Tippet claims that, “By turning houses into property, they have failed to fulfil their function as homes” (Tippet 2020, 80). The modular sustainable design approach could change the way people see their function in society and with the planet, creating an awareness of climate change.

Precht’s The Farmhouse, (2019.)

CONCLUSION

Overall, Split, Class Divides Uncovered, illustrates and informs the reader how the current class divide contributes and affects our society. The main goal of this essay was to understand how the class divide can be mended in order to repair society moving forward through the use of a cooperative model. By comparing different models and investigating the historical trajectory of cooperatives, the analysis supports the hypothesis that within the architectural realm cooperatives can be an effective tool to help bridge the gap in the class divide. Hierarchy and the concept of class has and will always exist, but by adopting a cooperative approach we can, as a society, begin to mend the gap.

“Class [is] a relationship of power that relates to work, ownership and wealth across the global economy” (Tippet 2020, 61)

By sharing the sense of ownership through the cooperative model, the power, wealth, and class gap that is derived from ownership of the upper class can be minimized. This notion refers to Tippet’s passage, “It is time to close the power gap and ensure that those at the top can relate to and represent ordinary people” (Tippet 2020, 65). Future developments of the cooperative model would stem from the employment of smart technologies which will act to further connect the classes together and mend the gap. The goal is not to abolish the class system, instead to repair it.

The Class Gap

Cooperatives – Mending the Class Divide? is a project of IAAC, the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, developed during the Master in Advanced Architecture (MAA01) 2020/21 by students: Rachel Busche, Morgan O’Reily, James Alcock, Alex Ferragu, Charicleia Iordanou, Rishaad Mohammad Yusuff; faculty: Manuel Gausa, Jordi Vivaldi.