Abstract

Expansion District is a studio project that explores future possibilities for housing in the Eixample District of Barcelona. The work follows a studio brief based on the city’s proposal to convert the Eixample into an array of interconnected superblocks. With a focus on human communities and big data analytics, this project proposes a two-part design thesis conceived to alleviate the worst effects of gentrification by taking an innovative approach to social housing.

Introduction

Social Housing in Spain

Barcelona has have fallen behind many other European cities when it comes to social housing. When it comes to housing policy, Spain has long put its focus on ownership. National-level housing policy has been focused largely on paths to ownership for decades. However, the issues addressed in this project primarily play out in the rental market. As it stands today, around 2% of Barcelona’s housing stock is dedicated to social housing for rent. In the Eixample district, there are only seven such dedicated buildings. The EU has set a target of 15% for social housing, and although that will not be universally achieved, Barcelona has a long way to go. This project takes a fresh look at how the city could achieve the EU target in the context of the Eixample district.

The Superblock Model

Despite its critics, the superblock model pioneered in Barcelona has been gaining popularity. Superblocks provide a much-needed respite from the density and urbanity of the city. They are a new form of public space and greenery for local residents. They reduce traffic and employ tactical urbanism to create a safe, comfortable gathering place for people to enjoy. Quality of life appears to increase in the immediate area around a superblock. Each one acts as a sort of urban acupuncture, bringing life and activity into the public realm previously dominated by cars.

Eixample as a Superblock

Given the positive outcomes of the superblock experiment thus far, the city has proposed an ambitious plan to convert the entire Eixample district into an expansive superblock array. Vehicle traffic will be rerouted to open green pedestrian corridors. Intersections across the district will be reclaimed from cars and repurposed into public squares. Tactical urbanism will be deployed across the district to bring a new focus on urban greening, recreational space, and local community amenities. The city’s plan proposes district-wide changes that will produce vast improvements in local quality of life. With those improvements, demand for space will also increase. People want to live in safe, attractive, and lively neighborhoods. Residents and visitors alike are drawn into pleasant urban spaces like those that the superblock creates. If executed successfully, the city’s ambitions to transform the Eixample into a superblock district will have far-reaching second-order effects. The district will become a case study in forward-thinking urban design. It will draw international attention amongst city planners, urban designers, architects, and developers. Those familiar with urban design principles know that this sort of change and attention usually leads to gentrification.

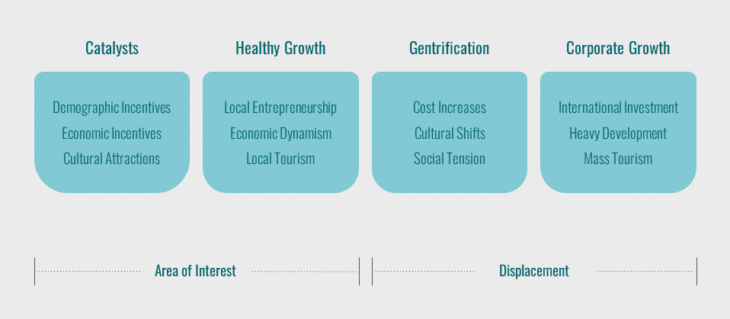

Gentrification

Gentrification is a complicated and often contentious topic. When the quality of life improves in a neighborhood, demand for housing by higher-income residents eventually increases as well. While there are many ways to parse the gentrification process, the following is one method of analysis that delineates where and how housing issues arise.

Segmentation in the Housing Sector

Is it possible to vastly improve the quality of life in a neighborhood without displacing lower-income residents? That is a question with no perfect answers. There are, however, long-standing principles of urban economics that can guide solutions. Increasing supply is the most obvious first step. More housing coming into the market eases demand-generated rent increases. Critically, new supply must be offered at affordable prices. Beyond that, there must be a mechanism that helps to equitably distribute existing housing amongst user groups. This is especially complicated in a diverse, growing, and highly international market like Barcelona. Short and mid-term users like tourists and international students drive up demand and can typically afford higher costs than lower-income residents.

Equitable Distribution

Increasing demand for housing must be met with effective mechanisms for equitably distributing space. The importance of this is demonstrated clearly in the conflict between locals and the onslaught of unlicensed vacation rentals on platforms like Airbnb. With limited housing available, the market tends towards favoring highly-profitable vacation rentals over affordable housing for locals, for example. The problem of how to distribute space equitably is exacerbated by market forces unleashed by software and technology. Software platforms like Airbnb are the reason why it is possible to allocate private residences to non-residents in the first place. They open the local residential market to a global pool of wealthy users with insatiable demand. Other elite global user groups like digital nomads are also the result of technological changes in the knowledge work economy. Proposals to alleviate the distribution problems that arise from these technology-driven market dynamics will likely also come in the form of software systems.

Intelligent Densification

Beyond the distribution of existing space, it is difficult to avoid extensive residential displacement in an improving neighborhood without building new, specifically affordable housing. The urban economics of this is obvious. What is less clear is where to build new housing in a district as dense as the Eixample. It is already one of the densest residential districts in Europe with over 35,000 residents per square kilometer.

An Integrated Approach

The best approach may be one that combines both intelligent densification and intelligent allocation of space. In practice, this means two things: 1) developing a software architecture that helps to allocate space equitably between user groups while actively reallocating existing space towards lower-income residents. In effect, this provides a countervailing force to the natural market dynamics that skew towards more profitable housing types. 2) Identify where the density of the district can be gently increased with the construction of new, affordable housing developments. This project outlines the studio process and outcomes of taking this integrated approach.

Process

Readings

Much has been written on the topics of gentrification, housing market dynamics, affordable housing policy, and so on. The studio team spent a lot of time absorbing as much material as possible at the outset. This project errs on the side of not suggesting much that is truly new. Instead, it makes an effort to push the conversation forward by proposing existing systems and design ideas integrated systematically and taken to their logical extremes. As such the initial readings on the subject explored existing research and design work on subjects from European models for social housing, to crypto-economics, to theories of gentrification, to Barcelona’s own publications on tourism and housing.

City Government Publications

It should be acknowledged that the Barcelona City Hall is likely one of the most forward-thinking and proactive government bodies in Spain when it comes to addressing urban problems like those discussed here. They have published extensive data and produced many reports on the subjects of interest. The city is, at the time of writing, executing on many different fronts. The government’s plans, although not uncontentious and politically disputed, are ambitious and well-founded. This project seeks to propose provocative variations on existing themes and to generally explore the space by engaging deeply with data, mapping, and urban design.

Data Analysis

Data analysis played a significant role in the design process. Large data sets from the housing platforms Airbnb and Fotocasa were analyzed using Python to reveal insights into the vacation rental and long-term rental markets. Both data sets were cleaned to contain only listings located in the Eixample district.

Airbnb Data

The Airbnb dataset contained all the units listed on the platform during 2021 in the Eixample. Findings from the code-based analysis found that of 5.115 listings, only 71% were officially licensed with the city. That indicates over 1.400 unlicensed vacation rentals in the district in 2021. The profit motive that drives this point is another finding from the data; the average nightly rent for a one-bedroom Airbnb in the district was €58. That makes a unit rented on Airbnb significantly more profitable than a standard long-term rental.

An additional analysis was drawn from data provided by the city to explore the relationship between the number of occupants and the number of bedrooms in the Eixample rental market. The most common Airbnb rental was a one-bedroom unit, which happens to be the least plentiful unit type in the district. This exerts a constraint on the supply of smaller units available to locals seeking long-term contracts. The most common household size (and the one project to grow most substantially over the next decade) is two occupants, yet the most plentiful unit type is a 5-bedroom.

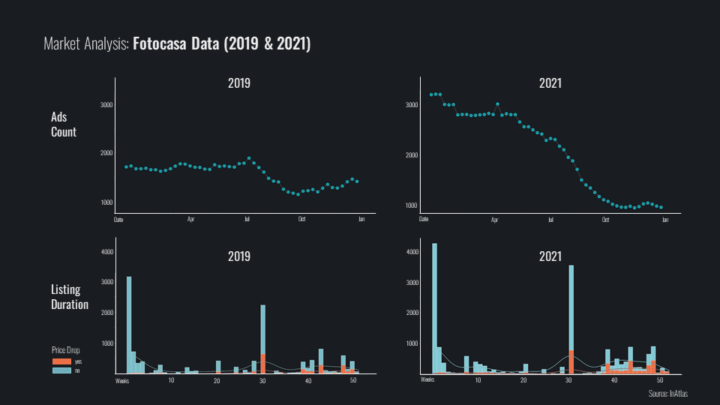

Fotocasa Data

The Fotocasa dataset contained all non-vacation rental listings posted to the platform in the Eixample during 2019. Again an analysis using Python revealed important market insights. Around a quarter (24%) of the apartments listed with Fotocasa in 2019 were rented within a week. Unsurprisingly, none of those units changed their asking price. Overall, only 20% of all listings were reduced in price before going off the market, but 50% of the listings were on the market for 7 months or more. If the listing duration is an accurate proxy for how long a unit sits empty while on the market, then the data indicates a substantial amount of poorly utilized residential space. This may be indicative of the mismatch between occupants per dwelling and the unit size outlined above.

This data analysis was then visualized using Kepler.gl to demonstrate the spatial distribution of the insights.

Project Agenda

From extensive research and data analysis emerged an agenda that defines the two primary fields of design work:

Equity: A software platform that addresses increasing demand for housing via the equitable distribution of space, and expands the proportion of space allocated to social housing in the district.

Density: A development schema that addresses the limited supply of housing by incrementally increasing density through distributed infill in the district.

Outcomes

Platform

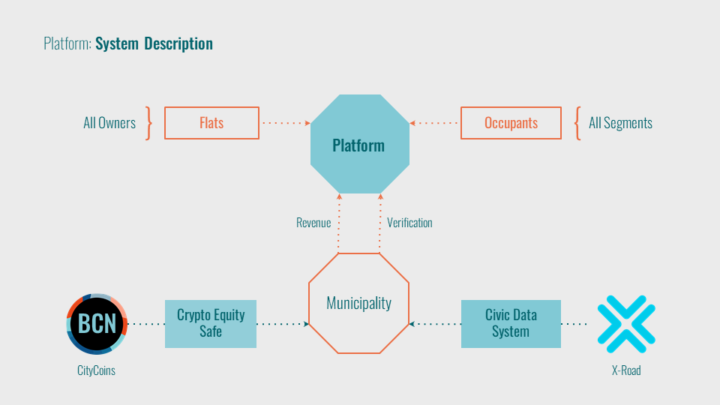

The rental market is made up of various landlords offering flats, and various types of occupants seeking a flat. Currently, every different user group finds housing through different channels. Tourists may use Airbnb while middle-class locals might use an agent or Fotocasa. Those who need affordable housing approach the city. The market is highly fragmented across many different platforms and agents. What if all the owners and all the occupants had one place to meet? From Airbnb owners to social housing departments, and everything in between. From tourists to those seeking affordable housing. All occupant types across all user groups, and all owners of every type of rental housing. One platform; one digital public market for rental housing in the Eixample. The platform would simply show occupants available units based on their needs, whether it be a furnished vacation rental or a long-term contract. Furthermore, what if all those who seek affordable housing could qualify for a housing subsidy from right within the platform itself? If a rent payment architecture could be built into the platform itself, then normal, market-rate landlords could rent to anyone in need of affordable housing since those renters would be shopping with a subsidy already in place on their account. This is a mechanism for turning a substantial proportion of existing private rentals into a form of social housing. For that to work, the platform would need to be connected to the city for verification of income and other civic data associated with users. Estonia’s X-Road civic data architecture demonstrates that such a system is already in use in Europe. The platform would also need to be connected to the city to source funds to fulfill users’ subsidies on the platform. This is simply to suggest that funds already earmarked for affordable housing programs be redirected through the platform rather than through various fragmented government offices. Additionally, new revenue could possibly be sourced from crypto protocols such as CityCoin. The CityCoin protocol has already raised millions in non-tax equity for cities in the US, and could easily be implemented in Barcelona, or anywhere else the platform operates. Crypto equity for municipalities is still a nascent field, but it is evolving quickly and it looks likely to be a plausible source of revenue to fund subsidies for affordable housing. Overall, what is unique about this platform architecture is that it expands the concept of affordable housing to include much of the market-rate rental stock without actually constructing any new buildings.

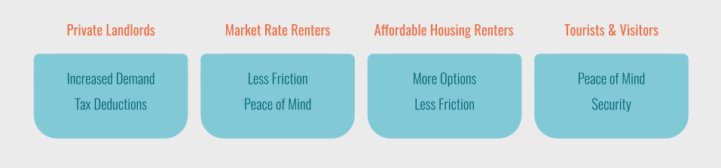

There are incentives for all stakeholders to participate in such a platform. Private landlords benefit from a larger pool of potential tenants as it would include those shopping with a subsidy. Market rate renters would enjoy less friction around rent and contracts as they are integrated into the platform architecture. Affordable housing renters would have more options to choose from since they can now access market-rate units. And tourists would get security knowing that all the rentals on the platform are licensed.

Development

Even with the platform in place, a limited supply of housing combined with a drastically improved quality of life in the neighborhood would result in unmanageable rent increases. Rent control is only a temporary postponement of market dynamics. Additional supply must be introduced where possible. But in a district already so dense, where is it feasible to build?

This is opening a longstanding and very contentious debate around density in the Eixample. Since its inception and initial implementation, Ildefons Cerdà’s master plan has been subject to change on the bases of increasing density. Cerdà’s original plan called for far more open space than one sees today. For better or worse, zoning amendments to increase the floor area ratio have increased the density of the district over the decades. These changes over time have resulted in an urban fabric where the building heights are not universally maximized. Buildings from eras with more conservative height restrictions stand next to those that were built higher in another era.

Using infill development to build on the rooftops of shorter buildings is not a new idea. Dual-era, dual-layer buildings already exist. In fact, there are currently both public and private organizations working to develop the existing air rights spread out across the rooftops of the district.

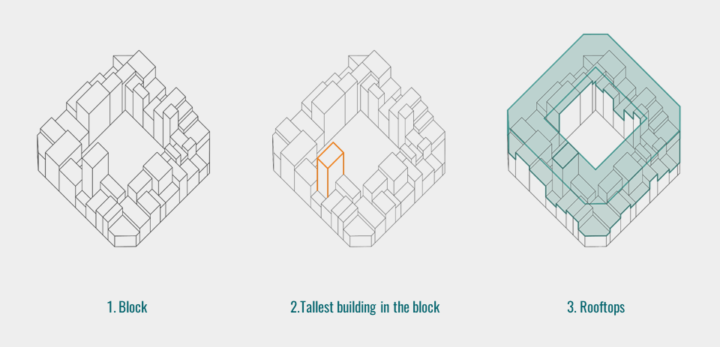

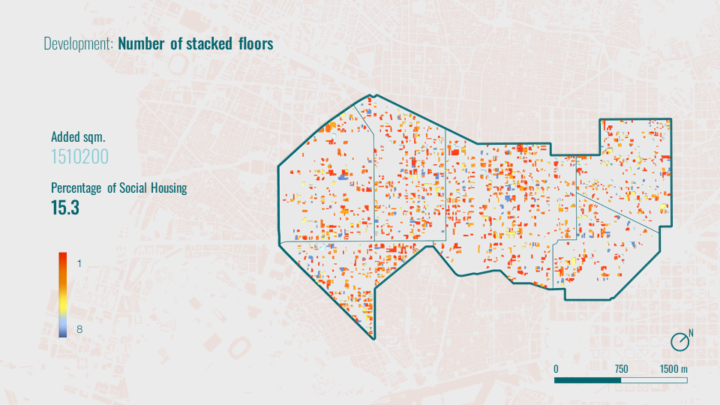

Determining how much space could actually be built is not an exact science and multiple approaches have been taken by various groups in Barcelona. In this case, floor heights by parcel were extracted from cadastral data to drive a Grasshopper model. The protocol used is as follows: take the highest existing building on a block as a local maximum, and develop the air rights of the other buildings up to that local maximum. In some areas, the effect wouldn’t be much more than a couple one-story additions per block as the building heights are already closely matched. In other cases like the one below, the additional space is extensive.

The Grasshopper function demonstrates the relationship between the protocol parameters, the spatial distribution of new space based on the existing fabric, and the amount of new space generated for new housing.

This parametric urban design approach is one way to roughly estimate how much of the district’s air rights are unbuild today. Not every building highlighted by the model will have buildable air rights of course, but the model stands to prove a point regarding the potential for densification in a district as dense as this. If the density is to increase yet further than it already has, it should be done intelligently, and gently. Finally, if the EU target for social housing of 15% were to be achieved in the Example, this is what it would look like according to the development schema proposed here.

Implementation

In reality, the model above points to the extremes; how much room is there, really? In practice, though, implementation is highly strategic. Where is infill appropriate and where is it not? More often than not it comes down to incentives. Which building’s current owners and occupants have an incentive to see the air rights developed? There are many condo associations wherein it would be an unproductive, uphill battle to achieve consensus. On the other hand, there are many buildings in dire need of improvement: from facade work to elevators, to energy efficiency upgrades. These buildings are the low-hanging fruit. How can new development on a building’s rooftop provide resources for the upkeep, refurbishment, and upgrading of the existing structure? The answer to that question holds the key to an implementation strategy that could be rolled out over time across the district.

Discussion

Densification & Character

The conversation around the relationship between density, character, and affordability needs to be had by each new generation with respect for the past and an eye toward the future. Barcelona and the Eixample district are internationally famous for their special architectural and cultural character. But like so many other beautiful urban places, we are now moving into an era where the Eixample could go on to become internationally famous for being unaffordable to those who long called it home. How can a balance be struck between preserving what makes the district special and keeping it from becoming an enclave for the rich? These are questions with no easy answers, but they are worth the trouble and tension of asking and attempting to find a compromise.

The Platform Economy

Jonathan Hoyles of Perk Labs summed up the significance of the platform economy when he said “platforms do not own the means of production, but instead the means of connection.” This is poignant for two reasons in this context. First, most of the incredibly successful organizations of the 21st century to date are internet platforms. They are multisided arenas that own the means of connection between people, rather than owning the means of production of goods. Second, cities can no longer be thought of as static entities that are slow to change and adapt. Cities are dynamic, full of data and information flows, and changing rapidly based on the actions of private technology companies. It is high time that cities themselves get into the platform business. If it is better to own the means of connection than the means of production, then cities are in an excellent strategic position to be successful at building and operating platforms. That is if they can source the talent, motivation, and political courage to act as boldly as a modern technology company would.

Crypto Tools

Crypto economics are still nascent in the municipal space, but teams are getting closer and closer to creating real, sustainable, and useful solutions for cities. The CityCoin protocol incorporated as a suggestion in this project is just one of many such projects that are aiming to supplement the time-honored traditions of municipal debt and taxation with municipal equity. There is a larger conversation occurring in this space around how to break free from the limitations of taxation into a world where equity financing and other concepts like universal basic income are a possibility in urban governance, but we’re not there yet. Still, things move very quickly in tech. Urbanists and policymakers should keep a keen eye on the future in this area.

User-Friendliness

Another important aspect of existing platforms like Airbnb, and existing data architectures like Estonia’s X-Road, is their user-friendliness. The incredible complexity of Airbnb as a software system is represented to the user in one easy-to-understand user interface. The vast pool of civic data organized and correlated by the X-Road system delivers, safe, fast, and accurate data access to divisions across the entire Estonian government. These software systems, whether database enabled or crypto enabled, offer simplicity and deep integration of data and services such that they are incredibly effective for the end-users. Municipal governments should take these examples to heart and make it a political priority to ensure that citizens receive clear, effective messaging about the municipal resources available to them. And when citizens access those resources they should work just as seamlessly. Without that level of user-friendliness, cities will always lose out to private tech companies that may not always have objectives that align with the values and aspirations of the city.

Conclusion

This project takes a creative and provocative look at potential methods of addressing housing issues that already exist in the city of Barcelona. The studio brief being the expansion of the superblock model across the Eixample district is just a future scenario in which these current problems would be worsened without intentional and careful intervention. The studio is a call for new paradigms in urban housing. What technologies can be used, and what design perspective could the city take to reform housing as a right for all people? These are the questions that underly this exploration. There is no shortage of technological tools to be employed… in the end, we need political structures that incentivize risk-taking at the municipal level. When we get that right, cities will fully enter into the platform economy as dominant technological players capable of acting nimbly enough to navigate the challenges ahead.

Rendition of the Expansion District at 15% social housing target

Expansion District is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at Master in City & Technology in 2021/22 by students: Aida Hassan, Kishwerniha Nagoor Meeran Buhari, Can Xu, & Ocean Jangda and faculty: Luis Falcon, Iacopo Neri, & Tugdual Sarazin