“A soil that has nothing to do with the Local and a world that resembles neither globalization-minus nor a planetary vision.” 1

Down To Earth by Bruno Latour argues —through a heavily political lens— for considering our global territory in a new way. Latour explains the convoluted situation of politics and justifies its chaotic condition with what he calls the New Climatic Regime. The goal of this text, however, is to suggest a new way of conceiving and therefore inhabiting the world, one which is connected to the soil but also aware of its global condition. 2

Latour politicizes nature and claims its inextricable connection with politics. He speaks of “Earth […]” as having “stopped absorbing blows” and “striking back with increasing violence” 3, making nature and therefore earth or “geo- […] an agent that participates fully in public life.” 4 Latour writes of two distinct ways of looking at the world or of being in the world: nature as universe or nature as progress. 5 He claims that human geography and physical geography are no longer distinguishable in the Anthropocene given that this “geo-” reacts to humans’ actions. 6 Latour remarks that what we know as the Earth is a Critical Zone, a mix of terrestrial species, which without them, would never exist. He speaks about the existence of an environment that is made up of terrestrials, that “the immensity of the universe” and the “boiling center of the planet” are quite unimportant in comparison, concluding “that everything that concerns [humans] resides in the miniscule Critical Zone” 7. In a way, we are sandwiched between two voids, the geologic world (rocks, magma, metals etc.) and the vacuum of space, Latour wants to refocus our attention to the thin, fragile membrane of terrestrials. What makes the environment is the congregation of species rather than an abstract geography. He highlights the need to differentiate between being on the earth as opposed to in it thereby breaking the historical hierarchy of humans as protectors or regulators of a distinct and separate nature. “‘We are not defending nature, we are nature defending itself’” 8, writes Latour referencing the French Sadists. It is through an exhaustive analysis of nature and our place within it that he later introduces how we currently conceive nature and our relation to it.

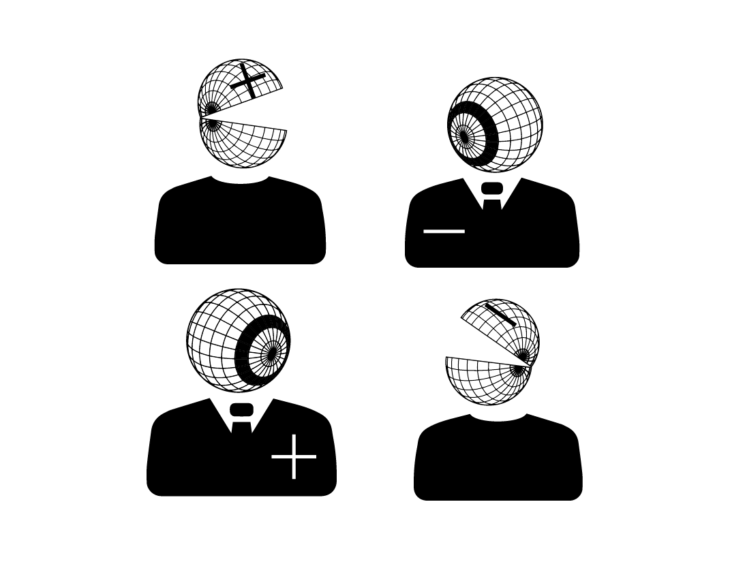

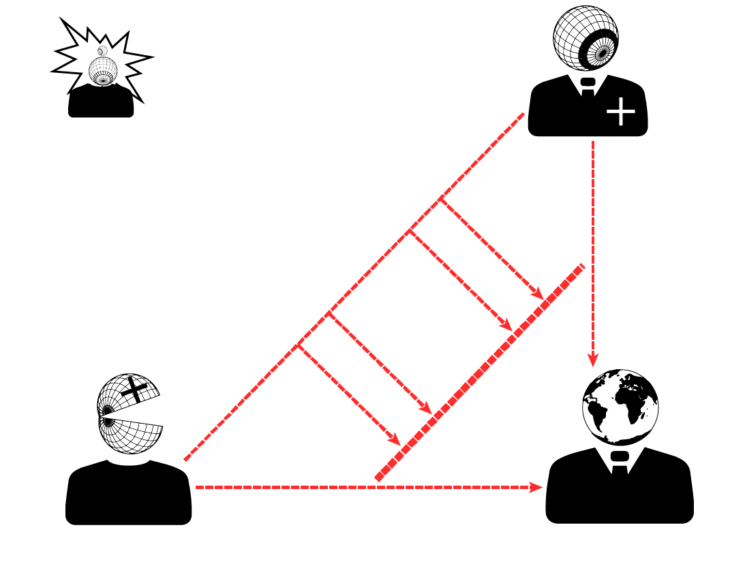

The four characters mentioned and developed by Latour. Illustrations by Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe.

Latour’s redefinition of nature is the base for unpacking the distinct perspectives of Global and Local, both of which ultimately lead to his final proposal of the Terrestrial as the only option to solve the climatic and by extension the political issues which affect the world. For Latour, “if nature has become territory, it makes little sense to talk about an ‘ecological crisis,’ ‘environmental problems,’ or a ‘biosphere’ to be rediscovered, spared, or protected. The challenge is much more vital, more existential than that.” 9. Here he combines both nature and territory, recognizing that while nature might be an abstract concept, something apart from us, territory immediately has a political connotation. Furthermore, he insists that changing the territory changes the politics because we, as a species in nature cannot be apart from it 10. He goes on to say: “Politics has always been oriented toward objects, stakes, situations, material entities, bodies, landscapes, places. […] It is object-oriented politics. Change the territories and you will also change the attitudes.” 11. Because of this seemingly unpredictable fusion of two “seemingly diametrically opposed” concepts,12 he illustrates the Global and the Local; two ways of understanding nature and therefore the world but both of which he refuses, believing they are insufficient to understand the world. Latour describes these “attractors” through illustrations and describes each one of them and their relationship to each other.

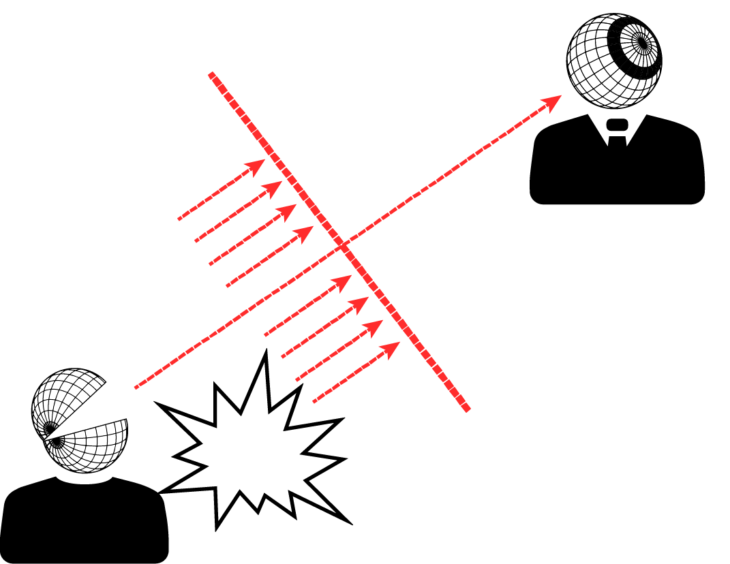

The dichotomy of Local and Global with the line and direction of modernist Progress. Illustrations by Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe.

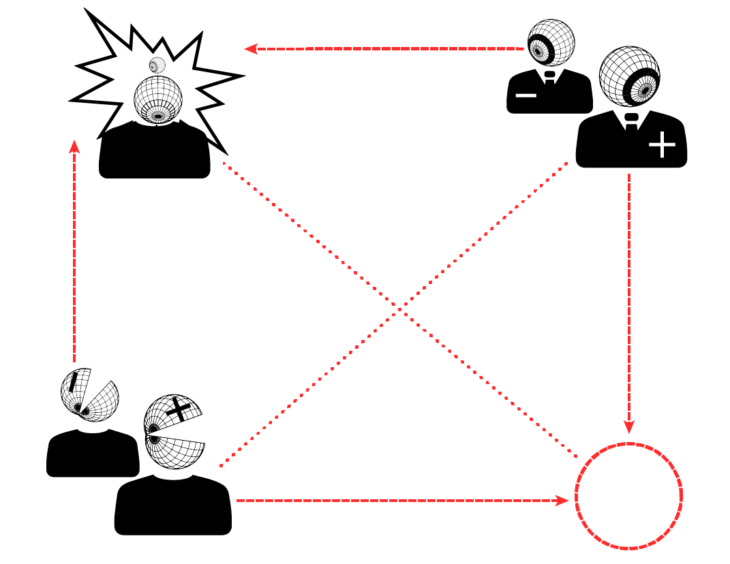

The first of these attractors, the Global, is a future looking “attractor” that pushes Progress forward no matter the consequences. Furthermore, the Global sees nature-as-universe, and seeks to understand it by gaining distance and effectively “losing one’s sensitivity to nature-as-process” —the Terrestrial proposal— “to gain access to nature as an infinite universe.” 13 This is illustrated as observing nature from a distant star —Sirius in Latour’s example— and avoiding the nostalgic and subjective associations that the Local has to the soil. This avoidance of the past or more local views of territory by the Global forces Latour to split this concept into the “Global minus” and the “Global plus” both of which share a common core ideal of the world but differ tremendously in terms of what they target. Global-plus, which looks for a utopia of diversity and freedom of thought given its scale, seeks to allow the connection of disparate individuals by releasing connections but also sacrifices to a certain extent the local identity for that connectivity. Global-minus, the “deviation of the modernization project” 14 on the other hand is so focused on the homogenization of culture and identity that it discards the Local plea completely. For example, Latour vehemently argues that “advocates of globalization-minus have […] accused those who resist its deployment of being archaic, backward and […] seeking to protect themselves against all risks.” 15 Furthermore, he believes that globalization-plus actually becomes globalization-minus through “obscurantist elites” or Moderns which had to stop “dreaming” of being alone in the world and be alone and use globalization —the promise of everything for everyone— as a tool for their own profit. 16 Although Latour heavily criticizes the methods of globalization, he recognizes it as a necessary part of the Terrestrial equation.

The introduction of the Out Of This World Politics character attracts both Local and Global minus from the terrestrial reality. Illustrations by Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe.

On the other hand, the Local attractor emphasizes identity and while criticized by the Global, has an intimate relationship with the ground but at times can be too narrow minded and “courageously defends the known against the unknown” (92). The Local-minus, as we have seen, becomes archaic and many times falls prey to what Latour describes as “Out-of-this-World-Politics” or “the horizon of people who no longer belong to the realities of an earth that would react to their actions”. 17 Instead, the Local plus truly defines who humans are given its presence in our quotidian lives. Latour believes “the ground, the soil […] cannot be appropriated. One belongs to it; it belongs to no one”. 18

Latour also analyzes the role of materialism and matter hoping to redefine it through the lens of the Terrestrial. Firstly, he criticizes the role of the aforementioned “Moderns” —who consider themselves “materialists”— reflecting on how unrealistic they are by asking: “How can one qualify as materialist […] who are capable of inadvertently letting the temperature of their planet rise by 3. 5°C?” He believes that the very definition of material —defined by the Moderns— is “hardly material, hardly terrestrial at all” given the abstraction that material has been through within the framework of the Global-minus. 19 Latour furthers his argument on materialism by connecting it to politics posing the question: how we can define class struggle more realistically taking into consideration a Terrestrial materiality? 20

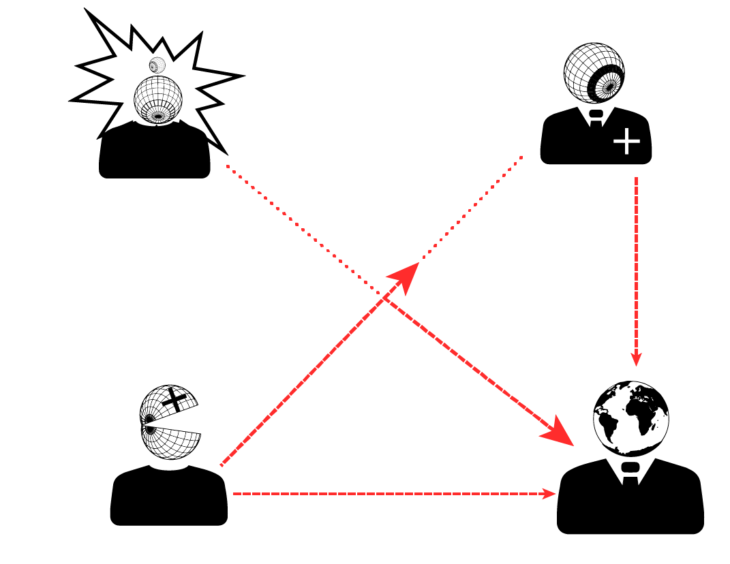

The Local and Global plus, according to Latour, must redirect their attention towards the Terrestrial. Illustrations by Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe.

To resolve the two opposites Latour proposes the Terrestrial as a viable model to continue to inhabit our “Critical Zone”. The Terrestrial means inhabiting both scales at the same time and “attaching oneself to a particular patch of soil on the one hand [and] having access to the global world on the other”. 21 His solution is to approach a reality that does not abstract the world to the point that the Critical Zone becomes unrecognizable and instead “is bound to the earth and to land but it is also a way of worlding, in that it aligns with no borders, transcends all identities.” 22 The concept stretches further than either of the Global definitions because it recognizes the past and the Local, unlike the Moderns’ ideals of Progress. At the same time, it “grasps the same structures from up close as internal to the collectivities and sensitive to human actions, to which they react swiftly” thereby addressing the anxieties of the Local. 23 This compromise is only achievable thanks to the processes that got us here, meaning that if the Local had not been ignored then the Global might not have gotten to the state of becoming the antithesis of its own goal, material, or matter for everyone. Latour goes on to describe the confusion that the Terrestrial might create from the Global point of view explaining how if one states that nature exists then one is too far away however if one is too close then one is criticized as nostalgic, subjective, and romantic. 24

The new line of Progress and direction drafted by Latour with Terrestrial as the focal character. Illustrations by Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe.

Given the plus/minus split between Global and Local, the Terrestrial may be similarly criticized. We believe the Terrestrial-minus could be easily translated as “green-washing”, where construction and policies alike among other things, are advertised as changing the paradigm when they seem to miss or completely ignore key aspects of the problems they are falsely trying to address. In conclusion, Latour synthesizes a contemporary politics in few pages and proposes a new way of considering an abused territory which has deeply affected politics and the state of the world. His proposal —the Terrestrial— brings together the complicated relationships humans have with the nature by accepting nature as us and swiftly positions us within its framework.

List of References

1 Latour, Bruno. Down To Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018., 2 Ibid., 92, 3 Ibid., 92, 4 Ibid., 41, 5 Ibid., 76, 6 Ibid., 41, 7 Ibid., 78, 8 Ibid., 64, 9 Ibid., 8, 10 Ibid., 52, 11 Ibid., 52, 12 Ibid., 92, 13 Ibid., 71, 14 Ibid., 92, 15 Ibid., 13, 16 Ibid., 20, 17 Ibid., 34, 18 Ibid., 92, 19 Ibid., 63, 20 Ibid., 61, 21 Ibid., 12, 22 Ibid., 54, 23 Ibid., 66, 24 Ibid., 72

“The Evolution of the Terrestrial; on “Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime” by Bruno Latour” is a project of IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, developed at Masters in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities in 2021-22 by:

Students: Pablo Herraiz García de Guadiana and Romain Russe

Faculty: Professor Jordi Vivaldi PhD