THE CASE OF MUMBAI-INDIA

Mumbai is a megacity and a World city, it has grown enormously since the 1950’s and gives a great case study of urbanization and its issues within an LEDC. This case study will explore how urbanization, suburbanization, counter urbanization and now reurbanisation processes have occurred in the Mumbai region and how those processes have been managed.

Mumbai is located on a peninsular on the Western coast of Maharashtra state in western India, bordering the Arabian Sea. Bombay is a thriving megacity that has had an economic boom in recent years. It is home to Bollywood and the film “Slumdog Millionaire” was based there. Indeed, property in Mumbai is becoming some of the most expensive in the world. One 28 story structure for one family cost £2 billion. However, many of the residents of Mumbai live in illegal squatter settlements (known as bustees in India). Despite the poor conditions in the slum Prince Charles thinks that the people of Dharavi “may be poorer in material wealth but are richer socially”.

Urbanisation and its impacts

Mumbai has urbanised over the past 60 years and urbanized rapidly from its origins as a fishing village. The site of the fishing village soon became a port region as the site favoured development. Protected from the Arabian Sea by a peninsular art the southern end of Salsette Island, it had access to sea on two sides and the British colonial administration in India developed the sheltered inlet into a major port. The British viewed the port and surroundings as the”Gateway to India”. This made it the closest port of entry to subcontinent for travellers from Europe, through the Suez Canal

The other significant factor to note is that slum dwellers make up an ever increasing proportion of the population, creating numerous problems for people and planners. It should be noted that the original urbanisation phase of Mumbai focussed upon the southern tip of Salsette Island, and outside of this the city suburbanised in a Northern direction.

The causes of urbanisation are multiple, but involve a high level of natural increase within Mumbai itself and in-migration principally from the surrounding district of Maharashtra but also from neighbouring states. Mumbai booming economy means that migrants come for job opportunities in the expanding industries, financial institutions and administration.

Mumbai has grown in a Northern direction limited by physical Geography as shown in the image below. It is limited in where it can grow with creek systems to the North and East, the Arabian Sea to the West and its harbour to the south East. Mangrove swamps further complicate the picture, and these marginal lands often form the location for the poorest people who live illegally in slums. One such slum is Dharavi, in the heart of Mumbai.

” Dharavi sits in the middle of Mumbai’s rail transit network, bordering the city’s emerging business districts. The economic potential of this land is nearly limitless, and investors have noticed (to the detriment of its residents) “

Who Benefits from Slum Demolitions in Mumbai?

Lacking the controlled façades of other great cities, Mumbai’s quotidian street life does not hide the poverty upon which “development” in the Global South depends. Throughout the city, one can see members of a vast, seldom-remunerated labor pool that does not share in globalization’s promises of plenty and exists on the legal margins. Sixty-two percent of Mumbaikars live on land to which they have no legal claim. Their “informal” lives play out in slums, in tucked-away settlements, and on the hot pavement of Mumbai’s many market districts.

In a country whose overriding challenge is rural poverty, India’s urban crisis has been a relative afterthought for the national government until only recently. India is 32 percent urbanized—a population of 377 million—and that figure is climbing steadily, although not at the pace of other emerging markets.

If current demographic predictions are accurate, six of its cities could have populations greater than 10 million within twenty years, while Mumbai and New Delhi will compete to become the largest cities in the world. But these cities are notoriously lagging in infrastructure to support this growth. Instead, the predominant thinking among Indian policy makers until recently had been to stem the flow of urbanization by way of rural development. Officials drew a distinction between urban and rural social spending, continually under-privileging cities.

At least in this regard, India’s rural bias is at odds with the elite consensus in development institutions. The most important neoliberal manifesto on urbanization, the World Bank’s Reshaping Economic Geography—a bellwether annual World Development Report released in 2009—envisions a world of burgeoning cities fueled by a transient, atomized labor force.

Mumbai’s poorest neighborhoods are not the result of enlightened planning, but where many of the world’s slums are synonymous with unemployment, Mumbai’s are incredibly industrious, marshalling the labor that anchors the broader urban economy. Mumbai’s leaders could not pursue their aim of “global city” status without the services that these communities provide. Business travelers in the city’s posh hotels unknowingly have their clothes sent to the hot tin shacks of Mahalaxmi’s open-air laundry, intricately designed to wash and deliver citywide. Thousands of office workers receive lunch from a slum-managed distribution system, which reputedly errs on just one in sixteen million deliveries.

The Positives of Dharavi Slum

There are positives; informal shopping areas exist where it is possible to buy anything you might need. There are also mosques catering for people’s religious needs.

There is a pottery area of Dharavi slum which has a community centre. It was established by potters from Gujarat 70 years ago and has grown into a settlement of over 10,000 people. It has a village feel despite its high population density and has a central social square.

Family life dominates, and there can be as many as 5 people per room. The houses often have no windows, asbestos roofs (which are dangerous if broken) and no planning to fit fire regulations. Rooms within houses have multiple functions, including living, working and sleeping.

Many daily chores are done in social spheres because people live close to one another. This helps to generate a sense of community. The buildings in this part of the slum are all of different heights and colours, adding interest and diversity. This is despite the enormous environmental problems with air and land pollution.

85% of people have a job in the slum and work LOCALLY, and some have even managed to become millionaires.

Local Based Improvements

Architecture students have also been hard at work. One student has created a multi-storey building with wide outer corridors connected by ramps “space ways in the sky,” to replicate the street. These space ways allow various activities to be linked, such as garment workshops, while maintaining a secluded living space on another. Communal open space on various levels allows women to preserve an afternoon tradition, getting together to do embroidering.

One student also tried to help the potters of Dharavi. He designed into existing houses the living space at one end and a place to make the pots at the other. Each has an additional open terrace on which to make pots, which are fired in a community kiln.

As the National Slum Dwellers Federation has repeatedly proven, housing the poor works best, costs less and is better for the environment, when the poor themselves have a say in what is being built.

Dharavi could also follow the Brazilian model, as evidenced in Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro. Within the Favelas the government has assisted people in improving their homes. Breeze blocks and other materials (pipes for plumbing etc) were given as long as people updated their homes. This is an approach known as SITE and SERVICE.

The Brazilian government also moved a lot of people out of shanty towns and into low cost, basic housing estates with plumbing, electricity and transport links. The waiting list for these properties was huge.

Suburbanisation in Mumbai

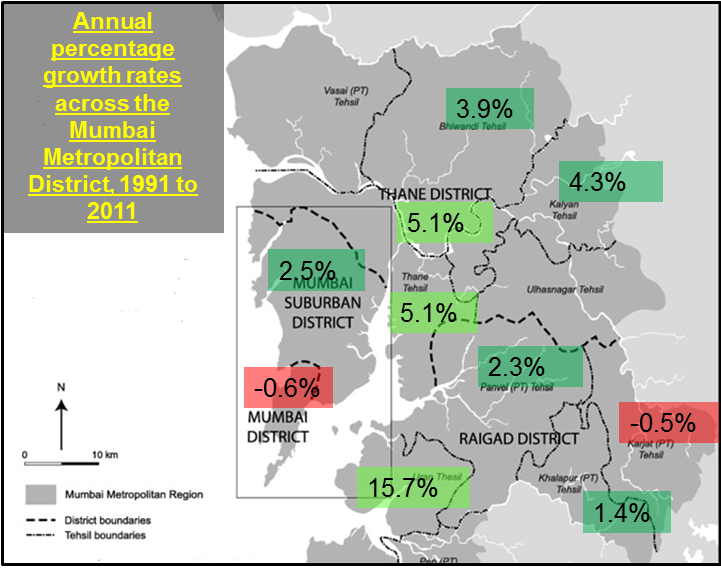

Mumbai now has a long history of suburbanisation, and many key events have occurred in the suburbanisation process, initially in a Northwards direction along major transport routes such as roads and rail links, and now in an Eastward direction. This suburbanisation has involved not just the growth of residential areas but also the relocation and growth of new industrial areas.

| 1930s to 1940s | The rise of Shivaji Park area, Matunga and Mahim as the outlying suburbs |

| 1960s (post independence) | Inner suburbs in southern Salsette and Chembur-Trombay had emerged |

| 1970s | Assimilation of the `extended suburbs’ beyond Vile-Parle and Ghatkopar. |

This suburbanisation has had consequences;

- People are economically stratified into those that can afford better housing and those that cannot, rather than historical caste, religious or linguistic stratifications

- Less than a third of the population of Mumbai lives in the `island’ city.

- The centre of density of population has shifted from the island city well into suburban Salsette.

- The commuter traffic has changed. Rather than being just one way into the Central Business District (CBD) in the south of the city in the mornings there is an increasing movement of people in the opposite direction. Increasing industrialisation of the suburbs is increasing this movement.

Well-established, decades-old informal communities often appear as nonentities on official maps, where they are depicted as green fields ripe for clearance and renewal. State authorities often view the slums the same way, ordering housing demolitions that benefit developers without remunerating residents for the lost labor and displacement.

Rental space in Mumbai is kept scarce by a regulatory regime that has frozen rents at pre-Second World War levels, which has resulted in a halt to all middle- and low-income rental construction. Since few but the rich can find rental space, Mumbai’s informal settlements are distinctly cross-class, housing middle-income workers and civil servants. Data obtained by longtime Mumbai urban planner Shirish Patel under India’s Right to Information Act revealed that more than 4,200 city police constables come home to extra-legal settlements.

Architects such as Das and planners such as Patel have made their own proposals to deal with one of the world’s most intractable housing crises. They call for low-rise architecture that, where possible, builds upon what informal communities have already developed, recognizing the resources and labor that informal settlers have already committed to their communities. Humanistic design principles, these voices argue, may incrementally improve the desperate conditions that exist in informal communities without destroying their social fabric.

Mumbai has retained an unsettling security presence in the wake of the 2008 assault that left nearly 200 people dead—the latest manifestation of a simmering ethnic conflict. Despite innumerable divisions among the city’s poor, collective action is likely the only vehicle by which slum dwellers will gain leverage over redevelopment schemes. Activists’ loud criticisms of the top-down, undemocratic process of urban planning in Mumbai arguably played a role in stalling bidding on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project in 2009. They have also loudly protested state-led demolitions. SPARC director Sheela Patel asserts that better organized communities get better deals from the state—provided they speak loudly enough to reach an opaque and distant development machine. (Mumbai has a figurehead mayor and most power is exercised at the state rather than the city level, with the largely rural Maharashtra casting a shadow over decision making.)

Informality is more than a legal designation; it is a social status and a political harness. Mumbai’s majority has little room to challenge the forces seeking to define them: an illegal existence coupled with the threat of physical displacement handicaps a population otherwise prepared to make claims on the state and to challenge an unfair economic system. Overcoming these barriers to participatory democracy could widen the political and human potential of millions.

References

https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/make-way-for-high-rises-who-benefits-from-slum-demolitions-in-mumbai

http://www.coolgeography.co.uk/A-level/AQA/Year%2013/World%20Cities/Mumbai/Mumbai.htm

Student : Mohit Chordia

Tutor : Gonzalo Delacamara