INTRODUCTION

Since we all have to work, the future of capitalism, and consequently the future of work, is a shared problem. The current state of work is a contradictory ecosystem of inequalities in terms of opportunities, salaries, benefits and rights. In order to elucidate the trajectory of the working landscape, Amelia Horgan retraces its evolution in her book Lost in Work: Escaping Capitalism.

She divides the history of work broadly into three distinct periods: Pre-fordism, or the introduction of the mass job framed across the end of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX; Fordism, the clear delineation of large-scale industrial work which emerged at the beginning of the XX century; and finally New work that embraces different typologies of work of the current century. In 2019 the spread of the Covid pandemic changed the New Work paradigm, apparently in a radical and permanent way. Before that time working-from-home was a special condition of few industries, but that surely would expand over time. Covid accelerated this process and since that time home became a space for productive labor, blending together home and work space, and suddenly introducing remote work in the range of New work.

RESEARCH QUESTION

Amelia Horgan’s Lost in Work presents us with a snapshot of the current state of work within the frameworks of capitalism and the post-pandemic world. Considering the current state of work within a capitalist system and its relation to the space of the home, our research question becomes:

How can the architecture of community housing alleviate the problem of house work?

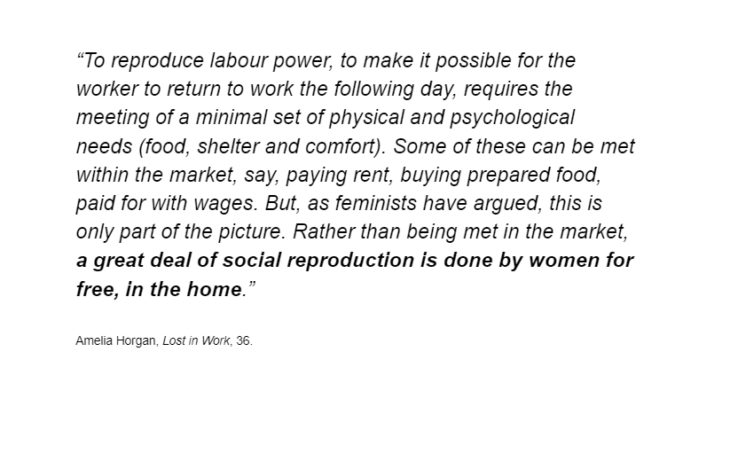

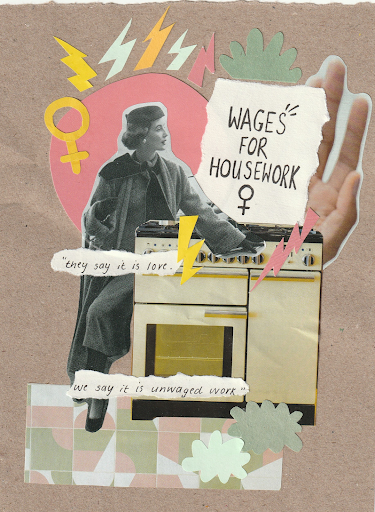

Horgan summarizes for us the feminist critique that an unrecognized, socially necessary labor was being produced by women within the home, which enabled men to work in the traditional labor space outside the home. The proposed feminist solutions to the problem of this unrecognized housework generally fell within 3 categories. The first category was the Individualist, market-driven approach, which focused on increasing women’s access to the job market, the hiring of service workers to do traditional domestic tasks and childcare, and increasing educational opportunities for women. The second approach sought to communalize the problem of housework. In the UK women established work communes to distribute the burden of domestic tasks. In the US, Angela Davis similarly proposed that the tasks of housework could be absorbed by industry rather than falling on individuals. Lastly, an economic solution to the problem of housework was proposed that in addition to communalizing housework, fair wages should be paid for women’s work within the home.

Looking at the current situation of housework we see many parallels to the problems that feminists were dealing with in the 20th century. Can we apply this framework to the architecture of community housing in order to deal with the problem of housework in the 21st century?

HISTORICAL TRAJECTORY

Looking back at our ancient civilization, agriculture and work were synonymous with each other. Homes revolved around farming and agriculture. There was no clear definition between labour and homes. Women took on a more nurturing role and men worked more on the manual labour front. In the 17th century, the putting out system came into existence. This system was similar to the modern day concept of subcontracting work. Textile manufacturers, Cotton farmers would hand out the work of weaving, stitching, etc, to women and men, and they would do this work within their homes

Throughout history, co-housing has always been prevalent. Before the rise of individualism and the nuclear family of the XX century, homes consisted of multiple families working together. With the industrial revolution, people started migrating to cities in search of jobs. In terms of housing, this led to ghettos being built for the poor and private residences for the rich. This revolution and it’s higher wages marked the beginning of nuclear families, but along with the world wars came the loneliness and need for people to live with communities again. With the massive upheaval of the World Wars, women started entering the workforce, both taking up the fordist jobs vacated by men who went to war, and through more flexible work such as tupperware and other in-home sales.

The idea of community living scaled up in parallel with the industrial revolution, with huge co-living facilities designed that incorporated factories and homes together as seen in the Utopian Phalanstere Communities. Modern day co-housing has also placed focus on shared ownership of buildings, and even involved cohabitants into the design and construction processes of their future homes.

HYPOTHESIS

Community housing and housework have been subjected to drastic evolution in a short period, understanding the historical precedences triggered mainly by constantly changing work paradigms. Anticipating the next stage of new-work post-pandemic through connecting the notion of cohousing with automation could have a significant potential to compatibilise the working and resting activities within the same domestic environment in the wake of previous feminist approaches.

Cedric Price designed the concept of the Generator (1976) that sought to create conditions for shifting, changing personal interactions in a reconfigurable and responsive architectural project.

“ To create an architecture sufficiently responsive to the making of a change of mind constructively pleasurable” – Cedric Price

To harmonise working, leisure, living and resting activities through automated-dynamic homeostatic components incorporating rules or preferred parameters for its evolution. House-work, by extension, can be subjected to the path of the desired outcome through spatial reconfiguration based on computational interpretation of habitual processes.

STATE OF ART

We identified a number of emerging technologies that could be used to improve cohousing including through design, construction, and maintenance of the built environment.

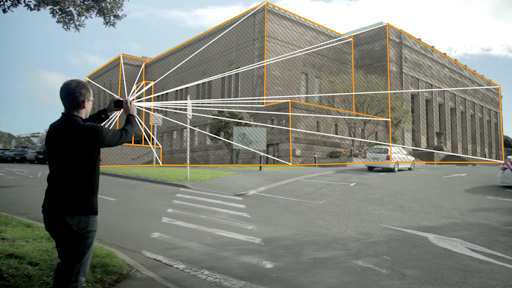

Augmented reality technology could allow any person to increase their skills in construction and thus become more self-sufficient and more able to manipulate their environment. 3D models are created and combined with BIM data. The building data is displayed digitally over the user’s physical surroundings in real time. Augmented reality is used in construction in numerous ways such as project planning, automated measurements, project modifications, on-site project information, team collaboration and safety training.

Self-assembly robotics, using small individual robots to create larger structures could also allow users to manipulate and customize their environments over time.

Collaborative robotics is another area where people could increase their abilities through a symbiotic relationship with technology. For example, the Arroyo Bridge in California is a highly complex parametric design, however it was built with minimal waste and using very few traditional supports by utilizing the precision of robotic arms along with the flexibility of human welders.

Lastly, a number of apps and other software exist on the market allowing people to work from anywhere and have more access to manipulating their environment.

CASE STUDY

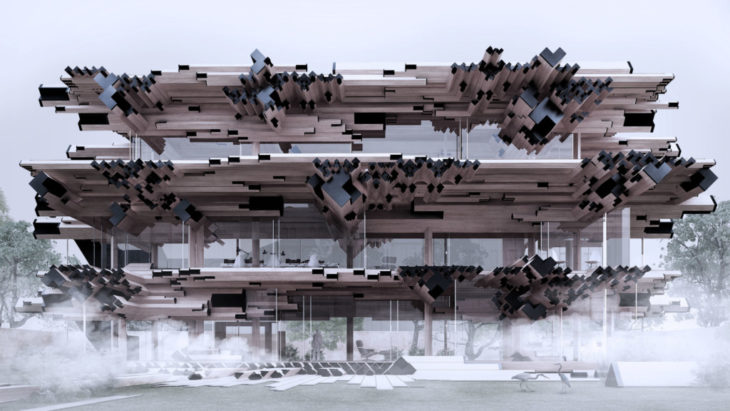

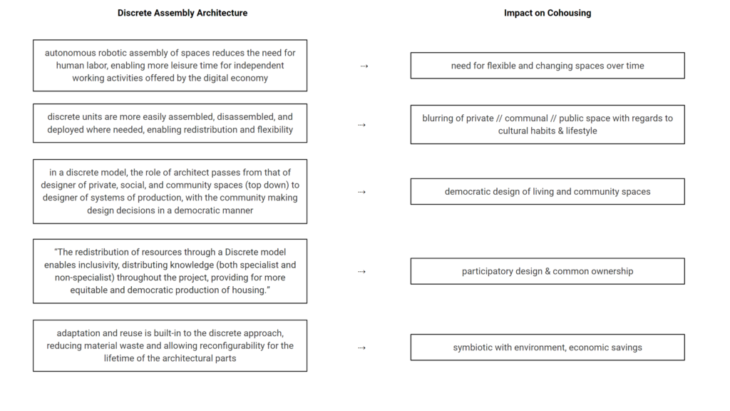

We explored Discrete Assembling and automation in the architecture of housing. We analysed this field of research through the work of Gilles Retsin, then moving on to the wider panorama of discrete assembly architecture. This is a strategy based on the design of discrete elements that can be easily assembled together offering multiple advantages in terms of automation of the fabrication and constructive process, convenience of use, mass customization and social involvement. We explored the potential of this research line in relation to our hypothesis, namely, how discrete assembling could impact the architecture of cohousing and how it can contribute to alleviate the problem of housework and working-from-home.

We have seen that a fully automated discrete architecture offers some possible solutions to the problem of housework as it applies to co-housing. However, it raises significant questions as well. While the role of the architect may shift from that of space designer to systems or process designer, how do we ensure that we are not simply “translating” the current approach from the analogue to the digital? By building discrete architecture algorithms within a capitalist market system how do we avoid reproducing existing hierarchies and prejudices of the status quo, repeating the mistakes of the modernist approach? These are questions that need further discussion and debate if we are to explore the possibilities of discrete architecture in co-housing seriously.

PERSPECTIVE

We would like to conclude with this consideration;

How could robotic and automated architectural interventions act as a social catalyst for community building? Is it possible for a radically new architecture to trigger new social relations in our communities?

Automated Labor Cohousing is a project of IAAC, the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, developed during the Master in Advanced Architecture (MAA01) 2020/21 by students: Angelo Desole, Arunima Kalra. Michael Groth, Stanislas Naudeau, Aishwarya Arun, Sabina Javanli & faculty: Manuel Gausa, Jordi Vivaldi.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Retsin, Gilles. “Discrete Architecture in the Age of Automation”, Architectural Design: Discrete: Reappraising the Digital In Architecture, vol. 89, issue 2, 2019.

Retsin, Gilles. “Digital Assemblies: From Craft to Automation”, Architectural Design: Discrete: Reappraising the Digital In Architecture, vol. 89, issue. 2, 2019.

Ayala, Adriana. “Breaking the architectural paradigm with Gilles Retsin – interview

Design for Gender Equality: The History of Co-Housing Ideas and Realities : DU Vestbro