The built environment though created and controlled by a few skilled individuals is widely used by thousands of humans who by being within the space, relate to their surroundings and are affected by it. The spaces that enclose or surround people effect how they feel and behave. In a scenario where unfamiliarity and distress is a constant state of being in the world today, our built environment should adequately provide for familiarity and dialogue. The world today is in need of empathy and the architecture we live and interact in should reflect the same. The position of the designer for bringing an intangible aspect to a project and their insight into quality of space, anthropometry, and aesthetics is essential. As the world takes a paradigm shift into the realm of automation, what is the step to take to make a more relatable built environment? This essay deals with how architecture has constantly kept up with a steady functional evolution but not an equivalent emotional or empathic mechanical and functional projects that are intrinsically objective can and should have a dialogue with the subjective.

Function and aesthetic can arguably be the main attributes behind architecture and how a space or environment is built. Throughout history the emphasis has been shifted sometimes in favour of aesthetic and then to function and sometimes the emphasis is shared equally. With functionality comes efficiency, structural performance and the intrinsic ability to serve or adhere to the purpose of the built environment. With Aesthetic comes beauty, relatability, familiarity and most importantly, empathy.

Empathy* is the capacity to understand or feel what another being is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another’s position. In architecture it is the ability of a space to render itself relatable to the user within it. The sense of inclusion, safety, approachability and the amount the building engages with a person. As with the case of emotional empathy amongst humans, there are many types of empathy displayed in architecture that vary depending on context, the era of the buildings, culture, climate etc.

*definition by Hodges and Meyers

Cognitive empathy is to put oneself in another person’s shoes. In general most designers do this: design for the common person as though they are one themselves. Architects and architecture has gone very near to perfection on this as well as very far. For most centuries architecture was a representation of power through churches, cathedrals, capitalistic towers etc. Some though have engaged with the society with relief housing, parks, conventional spaces, wedding venue s etc.

s etc.

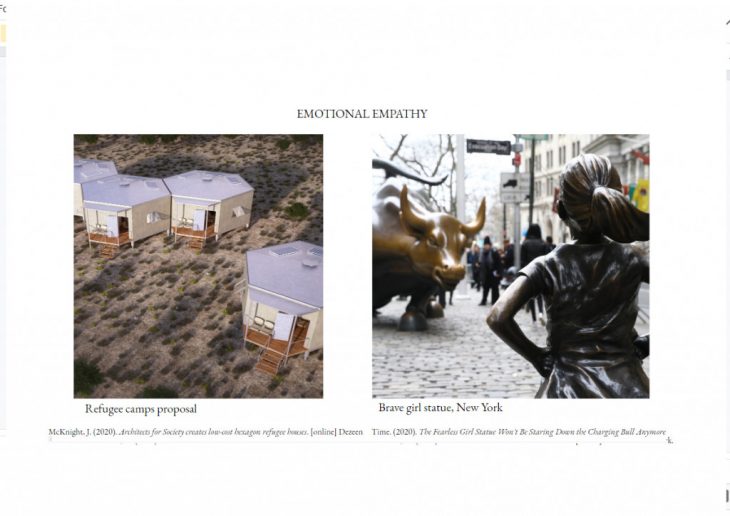

Emotional empathy is when one feels the exact same feelings as the person first experiencing it. It’s very hard and subjective to address this sort of empathy in buildings unless they dynamically respond to certain situations of distress like relief camps, shelters, government funded social housing, public installations aiming at promoting a cause, sudden organisations of peaceful or organised protests: these are manifestations when done right can illicit emotion and render support to the society.

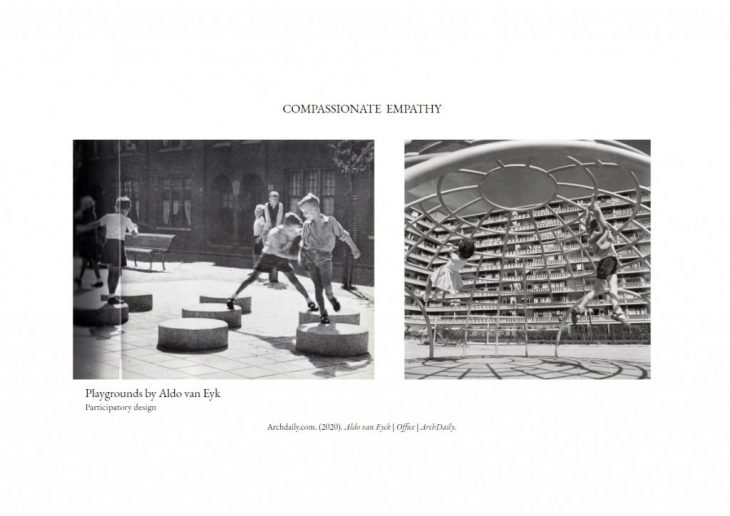

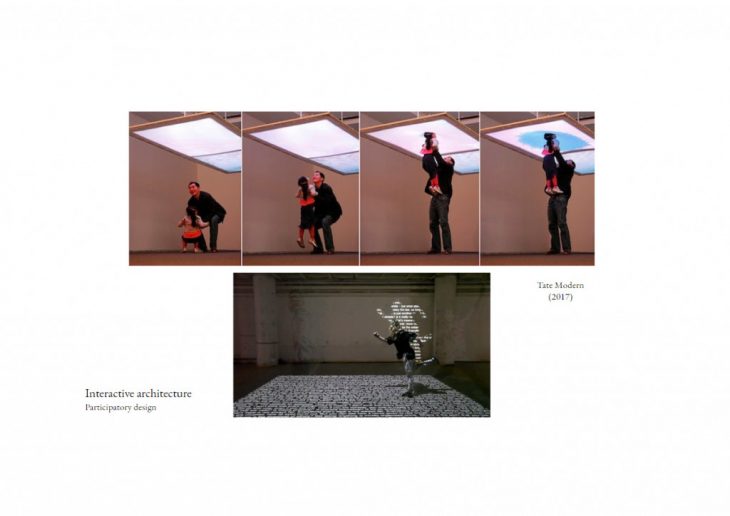

Compassionate empathy is rendered by actions. Participatory design can affect a person by actively engaging with them. Aldo van Eyck’s participatory design of parks and urban spaces. Bartlett’s e – flux project that deals with society actively taking part to build their homes through an automated process. Participatory design also invokes people’s investments and opinions for the greater good of urban public spaces and planning strategies.

How is empathy induced in architecture? There are various ways to create affinity between the subject and the person who is interacting with the subject.

- Colour and material (hapticity)

- Comfort and Ambience

- Proportion and scale

- Safety and security

- Integration with nature and natural process

- Climate and Environment

- Cultural and Social significance

All of these in combination with the intent and novelty of the subject can provide for an empathic experience

Empathy is subjective* and differs from people to people. It is very difficult or not yet addressed as to how to quantify or give an absolute value of a buildings empathic performance. Structural efficiency is easily validated by numbers but how to go about evaluating the users’ experience? There are some buildings that hold great sentimental value in people. For example culturally significant monuments are considered sacred and extremely important to a country and its citizen’s identity. The Taj Mahal gathers 7 million visitors per year. The burning of the Notre Dame generated one billion dollars’ worth of donations for its restoration.

There are some buildings that generate the opposite feeling where the human is exposed to alien and unfamiliar concepts. Peter Eisenmann’s House VI is an appropriate example where the inhabitants had to change their way of life to adapt to the house they lived in. The Tempelhof Airport is bare and represents fascist values that are evident to the people within who experience the space and instigate discomfort.

There are many case studies that succinctly empathize with their intent and subject. Based on the type of empathy and context, a study can be made on the degree or extent of empathy displayed in a structure. From this an evaluation can be made for building typologies of the future. To aid this, there are three types of empathy defined by psychologists: cognitive, emotional and compassionate and buildings can be classified into these categories as such:

The several of styles of architecture from Romanesque through gothic, baroque and neo classical had strict rules for aesthetic and had heavy symbolism and philosophy behind them. Even looking at styles from all across the world at the same time, there is a heavy emphasis on religion and symbolism in which people found solace.

The 1940s and thereon saw a sudden shift from the functional regime of edifices and moved towards the art and novelty side. Symbolism here was more obvious and was intended to engage and spark the person’s interest who would be in the space. Florals, motifs, mockery, biological shapes etc. were widely used to induce empathy though familiarity and convention.

| *note that there are studies on algorithms that are trying to quantify empathy so as to be able to use it in design processes |

Architecture has always been an explicit reflection of its social and economic progress. This can be seen clearly in the functional aspects of it. While the aesthetic depended on the trend and philosophy of the age, the function was determined by the state of the art of technology of when the structure was built. As mentioned before, function is a driving factor and for chunks of history, it determined most of how buildings were seen and constructed. For example, early settlements and civilizations made highly functional and contextually relevant structures. The disregard to aesthetics stemmed from the fact that they could be attacked at any time by neighbouring civilizations or natural disasters etc. The 1900s saw the subsequent “Form follows function” with architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier and movements such as the Bauhaus, De Stijl etc. evolved. This era was an ode to pre and post industrialisations when buildings were sought to be machines. With the advancement of computationally aided design tools, buildings of the present have a completely new ethos. Buildings are programmed to be responsive, adaptable, and efficient. In a way they are now predisposed and pre-programmed to be actual machines. Intelligent building systems with automated processes proceeded by robotic and digital protocols.

When buildings are literally controlled by parameters and how efficient they are as machines, where is the aspect of empathy? Do these parameters allow for an empathic experience? Is the resultant empathy or lack of empathy intended?

Currently buildings and mechanical processes employed in architecture look to achieve an end goal of efficiency, reusability, achieving a closed loop system, being responsive etc. The criteria of these buildings being aesthetic is then addressed as an addendum to its efficiency in an arbitrary fashion.

Perhaps the evolution of empathy should also be considered with the evolution of building typologies. Is empathy merely a passive outcome of a special experience or is one to actively achieve it. Consider various examples of interactive and participatory design throughout the years. The participation involves the lay person into shaping the experience of a built environment. The empathy can be given or it can be earned through participation. With the current context of technology, the aesthetic should be on par in an adequate manner and not just for adornment or decoration.

The idea of a building being a machine can be seen as the building being an empathic and systemic machine that through active involvement of humans can create an efficient system. The buildings of the future in collaboration of its inhabitants can become intelligent responsive systems. Can participatory design open new realms of empathy and how it can be achieved through active engagement with the building? Human’s cognition and empathy can play an integral part of defining and shaping the typology of upcoming buildings.

Respite in a courtyard on a sunny day, the play of light and shadow within a space, the volume and grandeur of a religious building; as important and profound as these nuances are, the architects roles is to find the nuances of today and what will come tomorrow.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Maggie Killington, Dean Fyfe, Allan Patching, Paul Habib, Annabel McNamara, Rachael Kay, Venugopal Kochiyil, Maria Crotty. (2019) Rehabilitation environments: Service users’ perspective. Health Expectations22:3, pages 396-404.

- Rikke Friis Dam, Yu Siang Teo(2018) How To Develop An Empathic Approach In Design Thinking.

- Christina E. Mediastika (2016) Understanding Empathic Architecture

- Nietzche, Friedrich. (1996)Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, 360. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

- Juhani Pallasma (2000) Hapticity And Time – A discussion of haptic, sensuous architecture, pages 4

- Greene, Robert. (2012)“See People As They Are: Social Intelligence” In Mastery, 125-166. New York: Viking Adult,

- Sean Joyner (2015) Exploring Empathy in Architecture

- 4 Pease, Allan & Barbara. (2004) “Seating Arrangments-Where to Sit and Why” In The Definitive Book of Body Language, 330-345. New York: Bantam Dell

- 5 Isaacson, Walter. (2008) “The Happiest Thought” In Einstein: his life and universe, 140-157. New York: Simon & Shuster Paperbacks.