Tall Ambitions Leading to Recessions ?

Dubai is a city in the United Arab Emirates that has undergone extremely fast development over the last century. While Western cities often transitioned from pre-industrial to industrial to post-industrial societies during the course of two centuries or more, Dubai has undergone such a transformation in only fifty years. As recently as 1955, the urban area covered a mere 3.2 square kilometers, and the majority of inhabitants lived in baristis,houses built in the Arabian vernacular constructed of palm-fronds. The first house using concrete blocks in its construction was not seen until 1956.

It’s nothing less than astonishing, then, that fifty years later Dubai’s built urban area was projected to exceed 500 square kilometers, and workers were building off of a foundation constructed of 110 tons of poured concrete. The engineering marvel would in a few years become the world’s tallest structure ever built when it rose to its final height of 2717 feet in 2009, a year before its public opening.

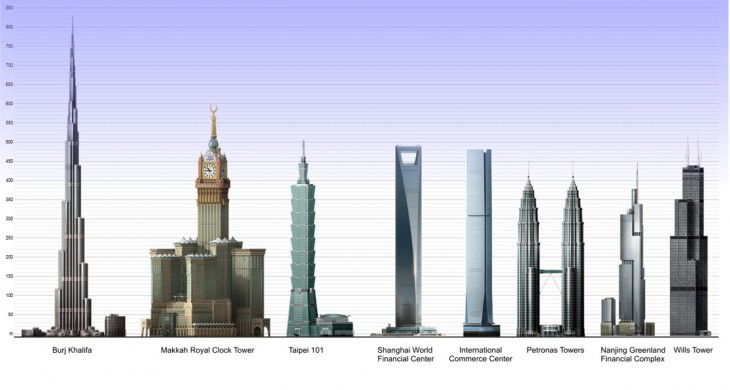

The world’s tallest building is a title that is loaded with symbolism, but it’s a symbolism that has evolved throughout the course of two centuries. Skyscrapers have long recalled images of modernity, economic power, and capitalism. But the world’s most recent tallest structures have shown how much has changed since the early twentieth century, when skyscrapers were built in city centers that required dense construction due to a lack of space. While this functional impetus for building up is still true for parts of the world, for example in Europe and America, the construction of supertall skyscrapers has taken on new motivations in other places. This is especially important since, as Donald McNeill notes, “of the world’s 15 tallest buildings, only three are in the US, and none are in Europe.” Indeed, it is hard not to notice that the building of skyscrapers has morphed into a thoroughly routine post-colonial performance.

The tallest buildings in the world as of 2012. Note: only one of these is located in the West.

What meaning do these structures take on in developing countries, then? For Kuala Lumpur, the construction of the world’s tallest buildings in the late 1990s was a strategy adopted to be an explicit symbol of national modernization for Malaysia. A decade later, the Burj Khalifa would take that sought-after title of world’s tallest building from Taiwan’s Taipei 101, and since then, proposals for the “world’s tallest” tower have popped up in Saudi Arabia, Azerbaijan, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Argentina. Kuwait’s Mubarak Al-Kabeer Tower and Saudi Arabia’s Kingdom Toweraspire to be the centerpiece of entirely new cities, while the Azerbaijan Tower would be placed atop artificial islands. What all of these proposals illustrate is the absence of functional motivations for high-rise construction. These conditions are not so different from Dubai, a city with ample space for development, especially considering the expanse of open desert surrounding the city. Yet this abundance of land hasn’t kept Dubai from building up, (or even out into the Arabian Gulf through the construction of the Palm Islands) a fact which is expressive of the city’s aspirations for global recognition. In addition to a desire to establish its own modernity, Dubai, like many of these other places, has aimed to use “iconic” architecture in its urban areas to market itself as a city worthy of investment in order to attract businesses and capital.

A rendering of Dubai new downtown after completion: a symbol of economic power?

The apparent economic goals of Dubai’s new developments are no mere coincidence. To provide some context, one can examine the political climate in which the Burj Khalifa was constructed.

Realizing that Dubai’s oil reserves would run out in a few decades, the emirate’s ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, aimed to diversify the economy by attracting businesses and manufacturing in addition to expanding the already sizeable tourist industry. Dubai’s gleaming modern architecture along with its various avant-garde projects were to be the main basis for sparking global interest in all of these sectors. Pursuit of this economic ambition has been made easier by the structure of the government’s influence on urban development. For example, in many Western European cities, the state generally takes a more central role in urban planning and development, while in American cities, planning is undertaken by developers with comparatively limited involvement by the city or state. Dubai, however, has developed a strategy that falls in between these two approaches, representing a hybridization of state control and economic liberalism in which “urban development is determined largely by the planning vision of the ruling family within an environment of market capitalism that seeks to attract foreign investment and reduce restrictions to free enterprise.”The result of this capitalist approach – which is at the same time state-run – is urban development that is essentially a spatial expression of the ruler’s economic strategy. The implications of this condition on the Burj Khalifa’s construction are twofold: firstly, it brings up the issue of political power and where it lies, and secondly, the true motives of the Burj Khalifa’s creation are then brought into question.

Part of what makes this situation unique to Dubai (and distinguishes it from most Western cities) is the centralized structure of the United Arab Emirates’ government. A constitutional monarchy, the Emirati regime limits the potential for most forms of democratic participation in urban planning for Dubai nationals, let alone the 80% of the population that consists of expatriates and migrant workers. The result is a top-down approach to development, and Dubai’s “differential economic growth leads inevitably to socio-spatial polarization between high-and low-income groups in society.” In other words, exclusive developments such as the Burj Khalifa serve only a minority of the population – the elite. This has resulted in distinct up-market portions of the city that practically segregate lower-income groups with very little outlets of redress available for com-batting their place in the city.

With such strong state backing for a project of this nature, the motives for the Burj Khalifa’s construction warrant even greater scrutiny. The desire to craft a “modern” image for Dubai has been established, but an additional aspect worth noting is the possibility that the Burj Khalifa was built to also prove the reputation of Emaar Properties. The largest development and real estate agency in the UAE, Emaar is partly owned by the Emirati government. Coupled with Dubai’s explicit economic strategy, it is clear that the conception of the Burj Khalifa was a calculated affair to promote government ambitions in more ways than one.

The Architecture of the Burj Khalifa

The Burj Khalifa as a building has been as polarizing as the city it’s built in. Critics have called it “pointless,adolescent lunacy,” and a “vanity project.”But despite the building’s detractors who largely take issue with the tower on a conceptual level for its ambitions to be the biggest in the world, the actual architecture of the structure is surprisingly refined. Karmin Blair wrote for Architectural Record in 2010

Iconic skyscrapers, especially those that strive for the fleeting title of “world’s tallest building,” are rarely the progeny of cold logic. Their backers invariably are motivated by ambition and ego. The architect does not control whether or where such behemoths are built. He or she can only ensure that they are proud and soaring things, not Frankenstein-esque, XXL-size monstrosities. Such is the considerable achievement of Adrian Smith, FAIA, and his former colleagues at the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in the gargantuan yet persuasive Burj Khalifa.

KarmiBlair echoes the opinions of other critics in asserting that what matters most in such large-scale developments is not the scope of the building, but rather its achievements in artistry that separate the tower from other sizeable structures. And the Burj Khalifa succeeds in this regard. An elegant structure of steel, concrete, and glass, the tower is clad in a shimmering skin to create a luminous sculptural mass that pierces the sky of downtown Dubai, as if to refocuses attention on the mainland away from the Palm Islands and the wildly constructed creations of the rest of Dubai.

But despite its grace and visual restraint in comparison to much of the surrounding architecture, the Burj Khalifa is still often criticized for its hubris. It’s important, however, to put things into perspective when addressing criticisms of the Burj Khalifa’s architectural indulgence. In an era of relatively new found priorities such as sustainability, for example, it becomes difficult to judge the accomplishments and failures of a building designed in the last decade by the standards and priorities of this one. It is similarly unfair to hold a building built in a city where summer temperatures regularly reach 120 degrees and even bus shelters are air-conditioned to the efficiency standards of other regions. While the Burj Khalifa is by no means a beacon of green design, its double-pane low-E glass panels make up a skin system that traps condensation that would otherwise evaporate. Such resourcefulness, while a small act for a building that will consume almost a million gallons of water a day in a region where water is such a scarce resource, nonetheless cuts back on water requirements by 20 percent.It’s worth pointing out, in addition, that such “unsustainable” levels of water consumption would be required for the 35,000 people the Burj houses whether they were to be situated vertically, as in this design, or horizontally throughout the city. In fact, this verticality and the corresponding promotion of urban density can be seen as “conceptual green rather than literal green,” as Karmin Blair puts it.

The Burj Khalifa towering over downtown Dubai at night. The Burj, like most skyscrapers, promotes the idea of urban density simply due to its structure. But during the other hours of the day when

temperatures can reach 120 degrees, will this conceptual sustainability be undermined by the lack of walkability of downtown Dubai ?

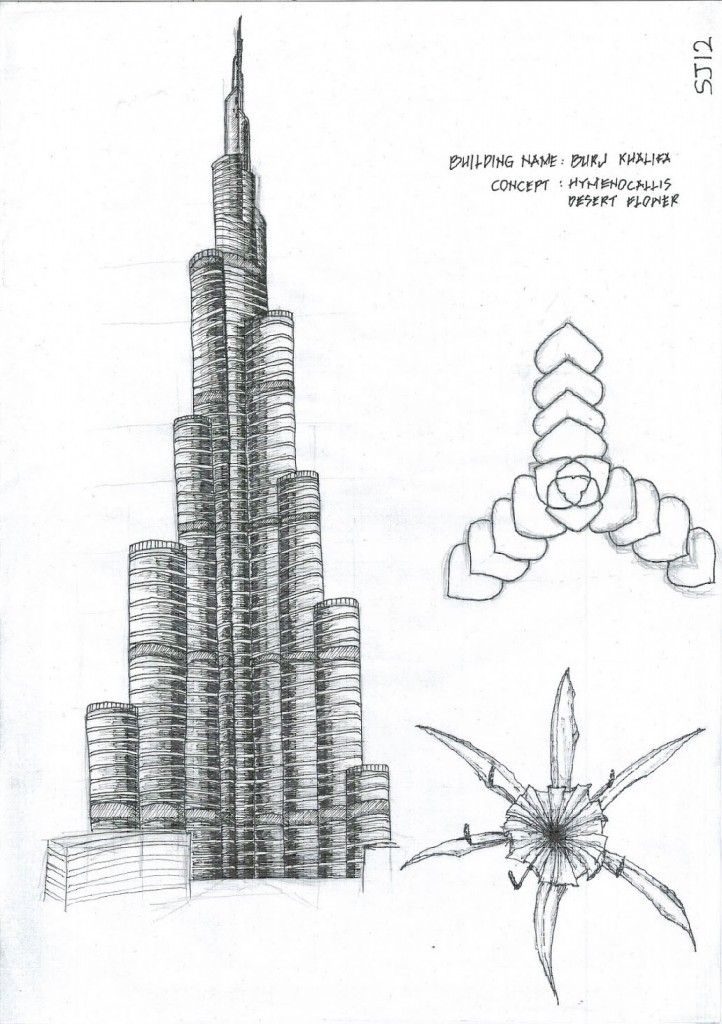

The Burj Khalifa spirals upward with a series of setbacks that gradually taper the tower to a slender end with a 700-foot spire.The Burj Khalifa is decidedly more organic, in part due to an effort to allude to local forms.The Hymenocallis blossom, a desert flower common in the Arabian Peninsula, inspired the tower’s triple-lobed footprint. The architects claim that the design contains motifs of Islamic art, and that when viewed from the base or the top, the tower “recalls the onion domes of Islamic architecture.”

As previously discussed, increasing development in the East has led to the evolution of the skyscraper and the symbolism attached to it. Another part of this growth is the increasing frequency with which architects incorporate local styles into their designs. In some cases, such efforts can prove to be a successful synthesis of modern building techniques and local traditional forms. But sometimes, the challenge of fusing standardized building systems with motifs that recall centuries of indigenous design history can end up looking like more of a simplistic caricature than homage. For example, onion domes are usually associated with the Persian and Mughal architecture of South Asia rather than Arab brands of Islamic architecture, yet the architect of the Burj Khalifa alluded to them anyway. Indeed, one wonders whether vague claims of reference to desert flowers and Islamic architecture in the Burj Khalifa were a central design ambition or part of an advertising campaign. Such interpretations are, after all, just that – crude interpretations of Eastern culture made by Western architects, and appeals to “exotic” sensibilities reveal an element of Orientalism in their marketing.

Conclusion: Moving Forward after the Recession

For many, the success of New Dubai was an affirmation of the Western neo-liberal dream, but a few years and a market crash after the global recession of 2008 have caused some to back away from such associations. The subject must be approached with consistency, however — as previously discussed, some have criticized the development of Dubai using double standards. These criticisms are further amplified by the complex relationship between Dubai and the West, as it is a city that often bears the brunt of criticism in its alleged “culture of extravagance” despite being largely conceived by Western designers.

Rem Koolhaus writes:

What has fascinated me in Dubai is how dominant our reading is. By “our” I mean the West. Dubai happened; we participated in its construction. We were complicit in its extravagance. But we were also the first to denounce its absurdity. What I fear, now that we have declared the “end-game,” is that we will also be the first to tell Dubai not to be itself anymore, to tell Dubai that it’s over and to declare prematurely an end, not only to an experiment, but also to a real cultural change that has been taking place in and underneath all of this, and that still deserves to reach its own conclusions.

Certainly, it is too soon to determine the lasting effects of a building constructed two years ago. But the Burj Khalifa, and all of the development related to New Dubai have undoubtedly changed the city and the region in profound ways, for better or for worse. The Burj Khalifa continued the trend of shifting symbolic power of skyscrapers from the West to East, and it furthered the challenging of established norms of what a skyscraper should be, where it should be built, and why. Above all, New Dubai was, and continues to be, an experiment in the intersection of social, political, and economic change and its multifaceted relationship to architecture.

Tall Ambitions Leading to Recessions is a text of IaaC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia developed at the Master in advance architecture in 2015/2017 by:

Students: Goutham Santhanam

Faculty: Gonzalo Delacamara