Gentrification

Gentrification refers to the process of renovating deteriorated urban neighborhoods by means of the influx of more affluent residents.

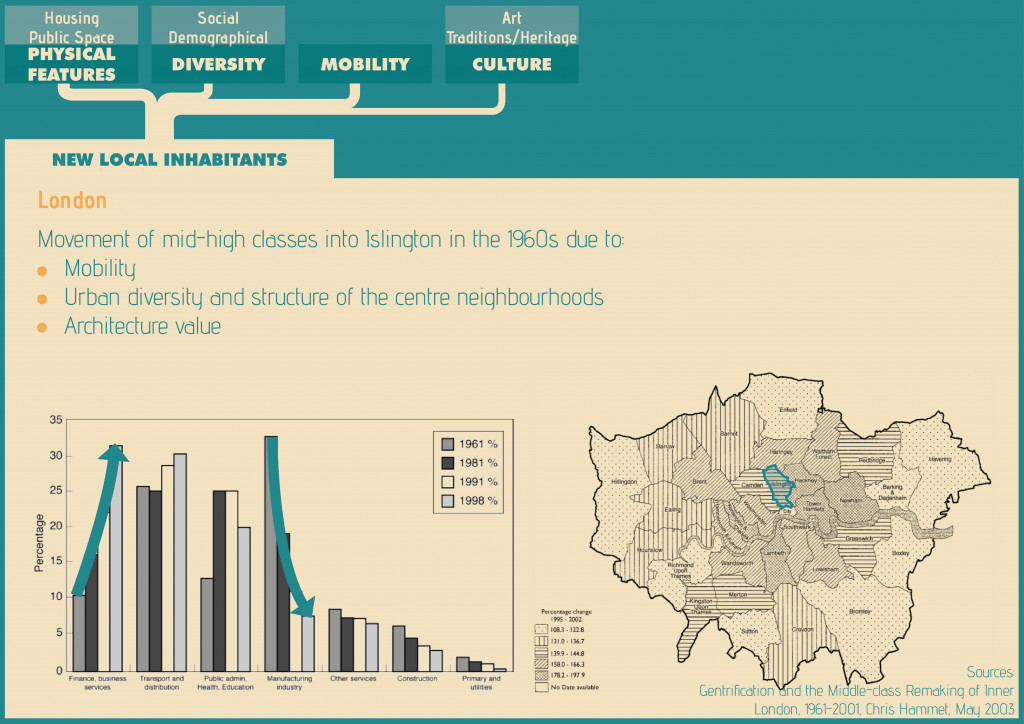

Gentrification orginally comes from the English word Gentry, which evolves from the Old French word genterise, and means of noble birth. The term was first used by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964.She was studying the new movements inside Greater London, and detected an increase of Londoner of middle-high class moving back from their outskirt neighbourhoods into central areas of London like Islington. They came form a change of the employment structure in London, where a shift from blue collar to white collar jobs was happening. By moving there and refurbishing mews and Victorian Georgian and Victorian houses, they displaced the lower income classes that populated the area. She concluded they were after culturally and urbanely richer and more diverse areas.

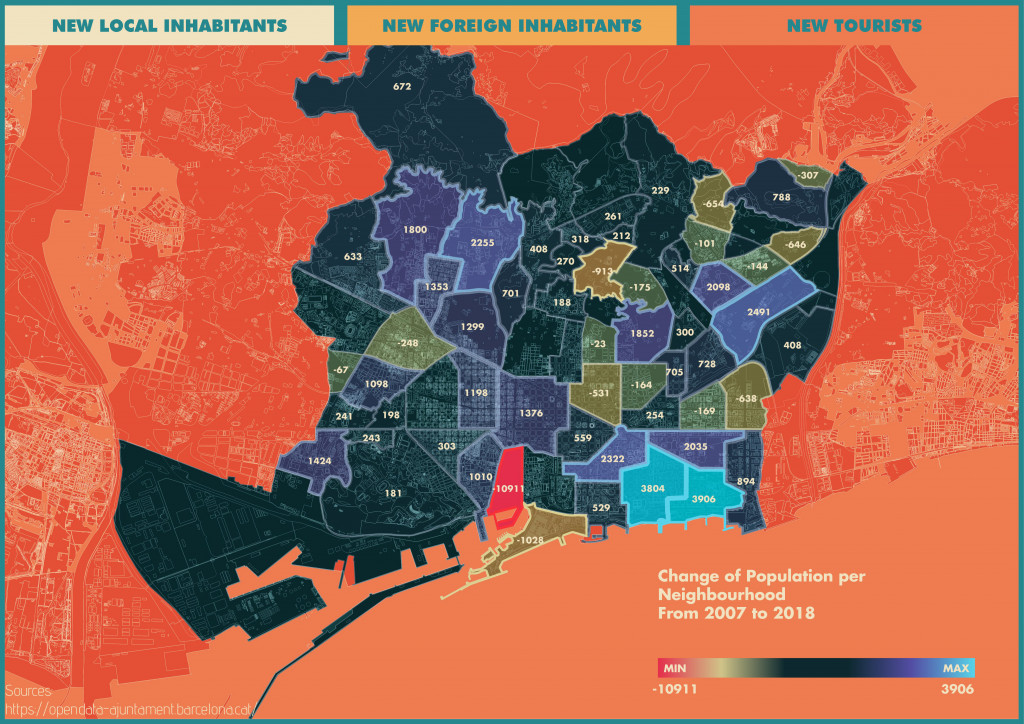

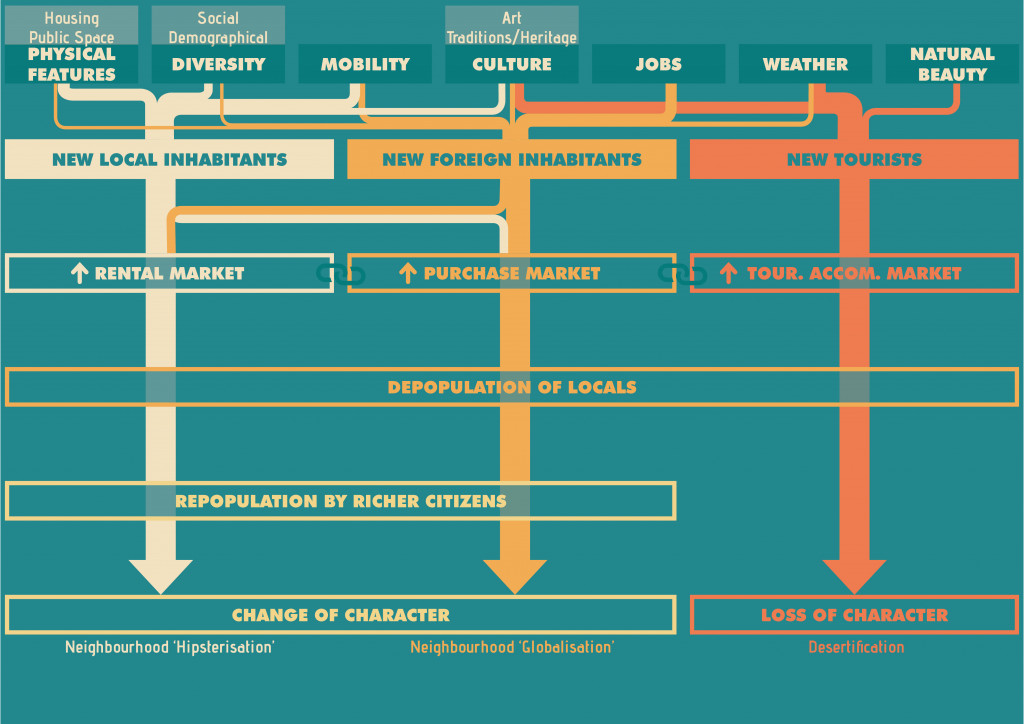

Gentrification is an issue that is now being faced by majority of the metropolitan and growing cities of the world. This often leads to a radical shift in the neighbourhood’s economic status and ethnic composition. But what is often confused or misunderstood are the types of displacements that happen during Gentrification. While local depopulation or displacement is a phenomenon common throughout the process of gentrification, the reasons for the movement are often varied and ignored in the light of common factors like real estate development and business expansion.

Gentrification can be mainly classified by their causes into three types which are Inner Gentrification, Outer Gentrification and Touristification.

Inner Gentrification

Inner Gentrification is one of the first types of gentrification with many prominent exmaples throught the growth of the cities of the world, a notable one among them being London in the 60s.It refers to the displacement of locals of an area by the people of a neighbouring area of higher income within the same region.

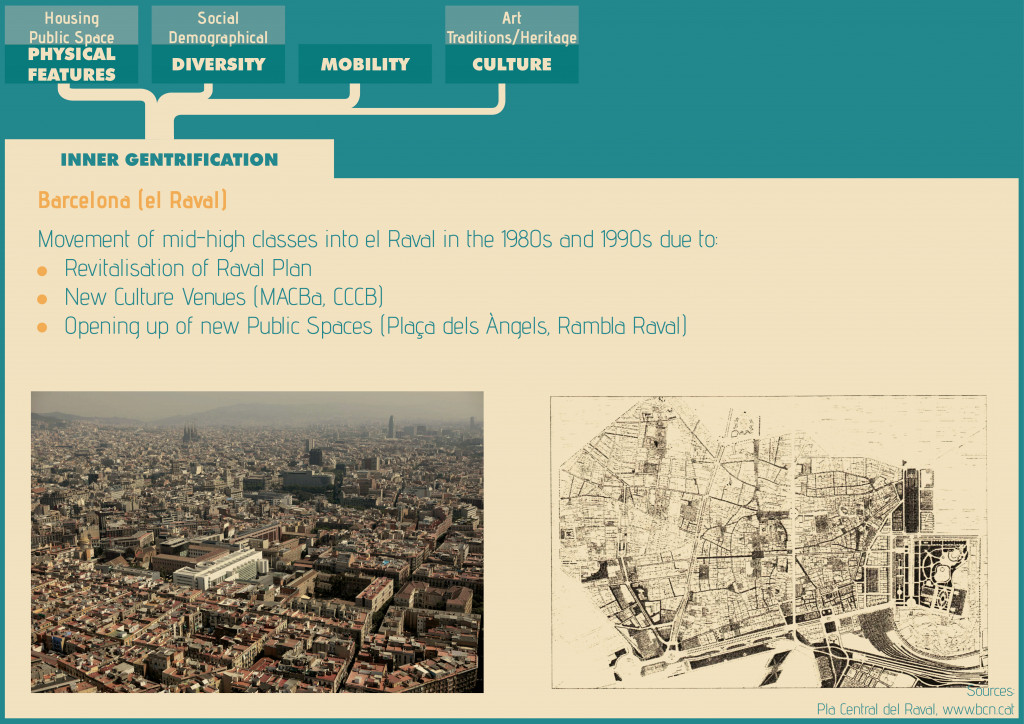

Barcelona has also gone through a phase of inner gentrification during the revitalisation of the El Raval neighbourhood.The Raval was an area were the low hygiene and lack of services pushed the lower income citizens to that area which in turn made the area more prone to dangerous activities and closed a vicious circle.In response to this situation the city council developed a Plan for the Renovation of Raval that included a very similar model than that of le Marais in the 1970s.

Outer Gentrification

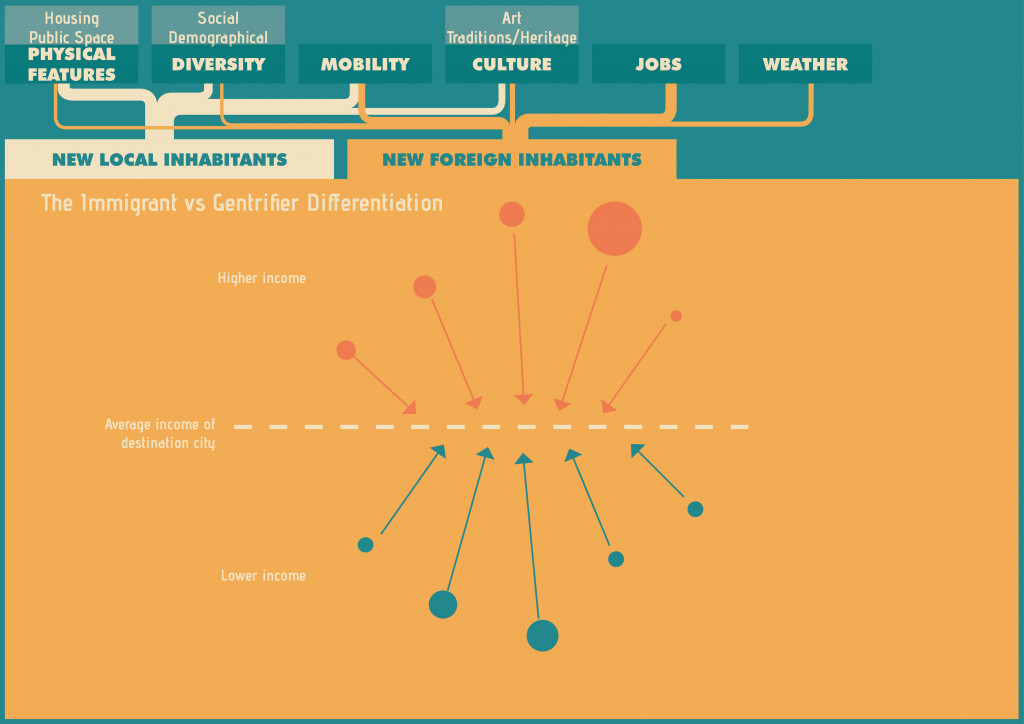

Outer Gentrification is a phenomenon that is relatively recent in comparison to Inner Gentrifcation that occured in response to the exponential increase in the number of global cities and their accompanying technology.It refers to the depopulation of locals by foreigners of higher income.This has been prompted by the increase of global mobility,cheaper methods to get around the globe and the explosion of media that enables people to get closer to any culture around the planet.

This can be explained in numbers by looking at the people that migrated in 1990 in comparison to the number of 2017. The figures have multiplied.

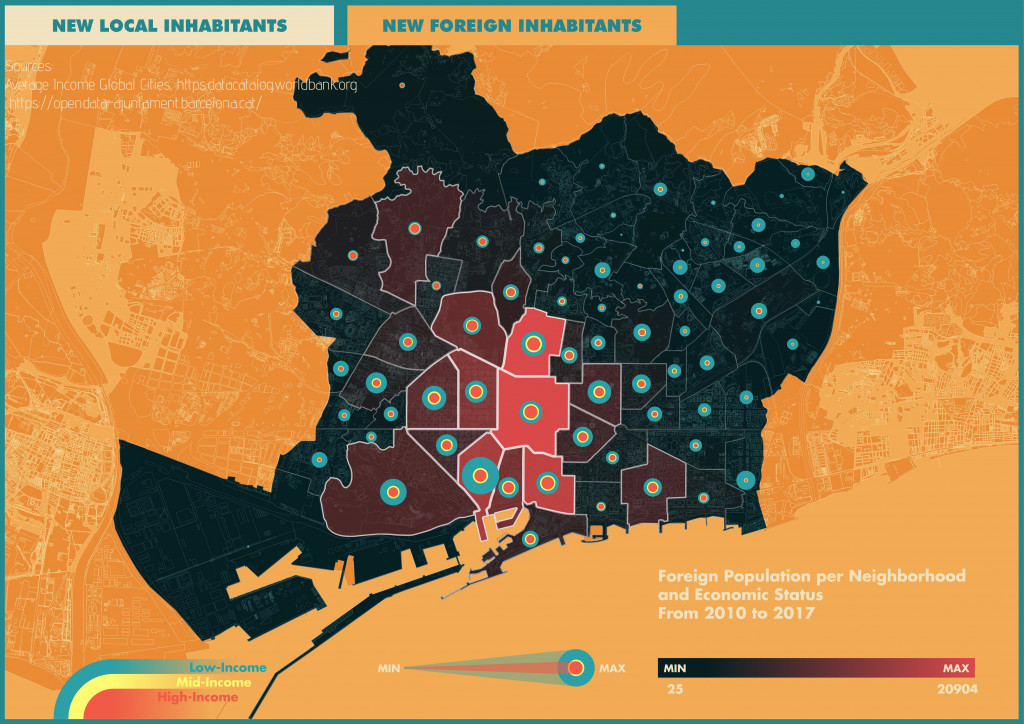

However, an important distinction is to be made between the immigrants and the gentrifiers. In a nutshell, immigrants are citizens of low income that come somewhere that has a higher income average, in hope to improve their lives. As a citizen of low income, an immigrant is usually pushed to the areas of lowest income of the city, and will cover the lowest side of the demand. They do not gentrify. A “gentrifier”, on the other hand, would be someone of higher income, that moves somewhere of lower income, moved by a series of attractive points and is able to find a higher value in their income.

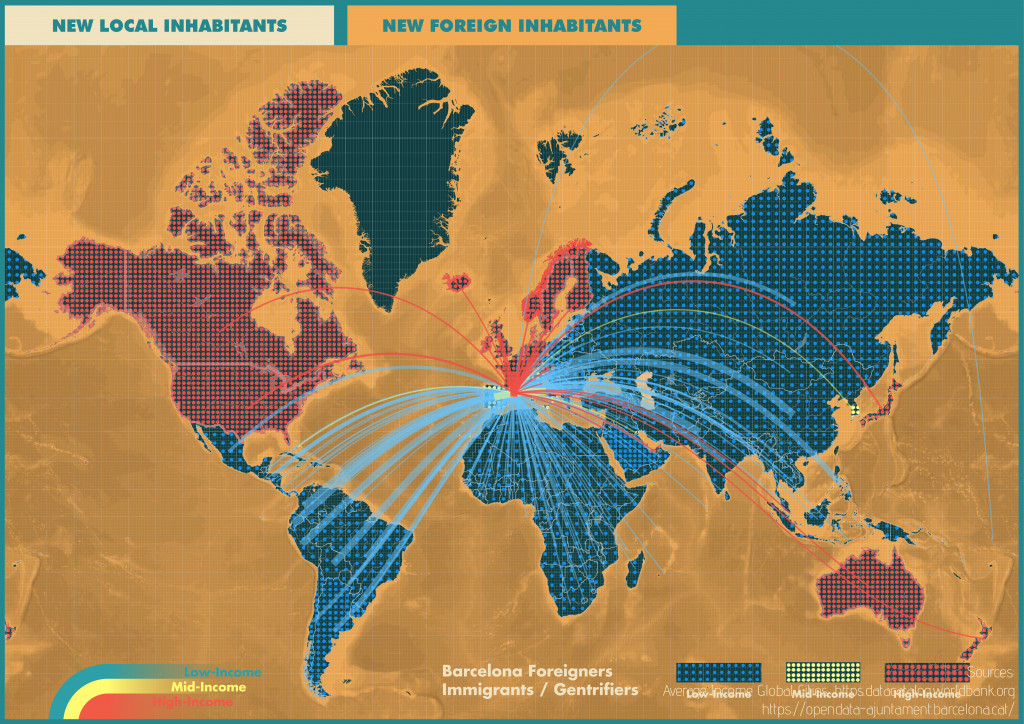

This is particularly important to keep in mind in the case of a city like Barcelona which became a global city approximately in the late 90s. As a global city, Barcelona stands virtually in the very middle of all global cities, when it comes to the average income.

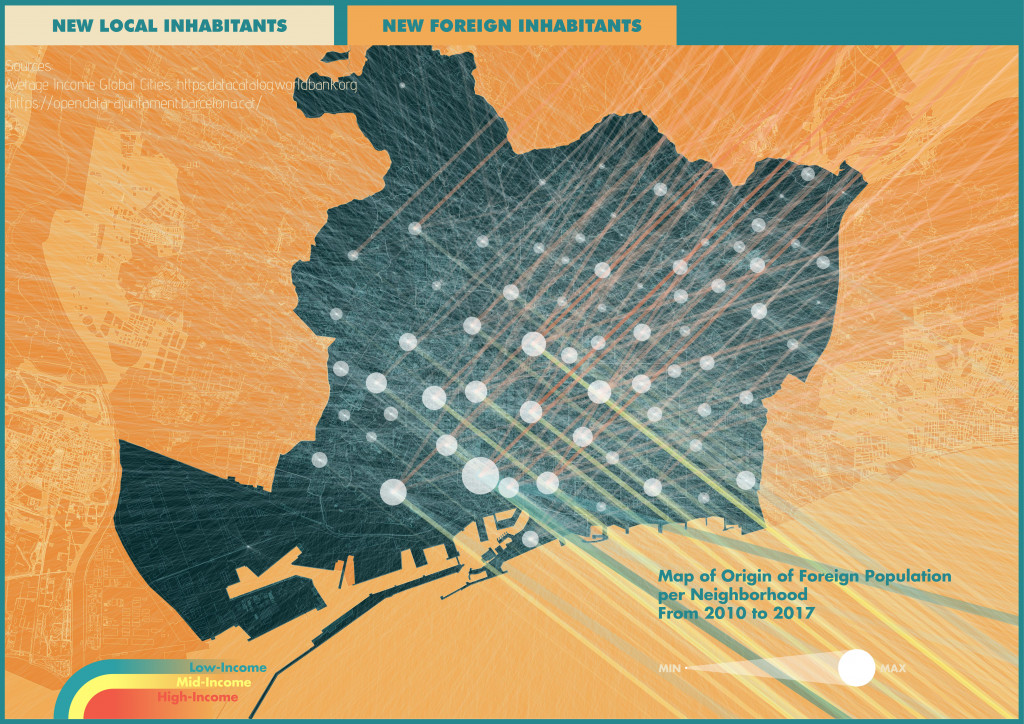

Upon investigating the number of foreign residents per neighbourhood and the average income of their country of origin, it is possible to distinguish between gentrifiers and non gentrifiers.

Touristification

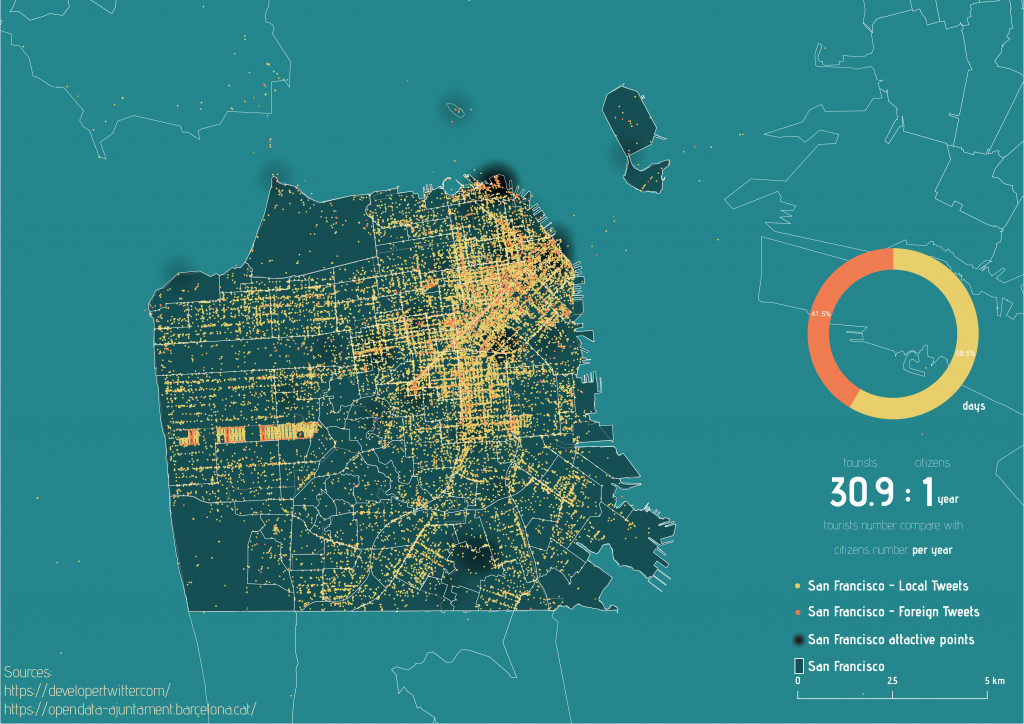

The third and most controversial of the three types of “gentrification” mapped is touristification. This process shows some differences with the previous ones, although most of the externalities that are inferred are shared with the other two types. Being a process that stemmed from tourism, it is interesting to note the exponential rise in tourism worldwide and Barcelona in particular and the impact it has had on respective cities experiencing mass tourism. The impact while vast, has both positive and negative sides.

On the positive side, cities like Barcelona earn a significant percentage of its GDP from tourism and also leads to its beautification or embellishment.On the other hand, mass tourism leads to significant loss in the quality of space and skyrocketing of prices which further incentives locals to move out of their neighborhoods in search for cheaper and quieter alternatives.

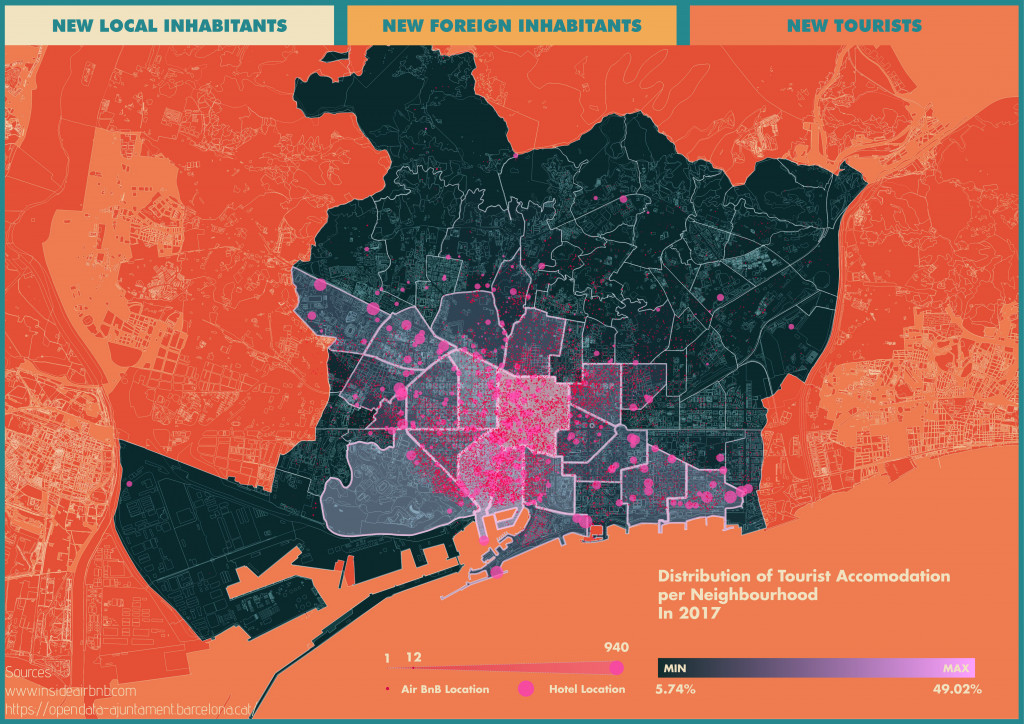

In case of Barcelona the touristic pressure can be mapped by simply rationalising the population of each neighbourhood with the concentration of Airbnbs and Hotels.It is interesting to note that the depopulation of locals is at its maximum in proportion to the number of touristic accommodations in proximity.

Economic Impact of gentrification

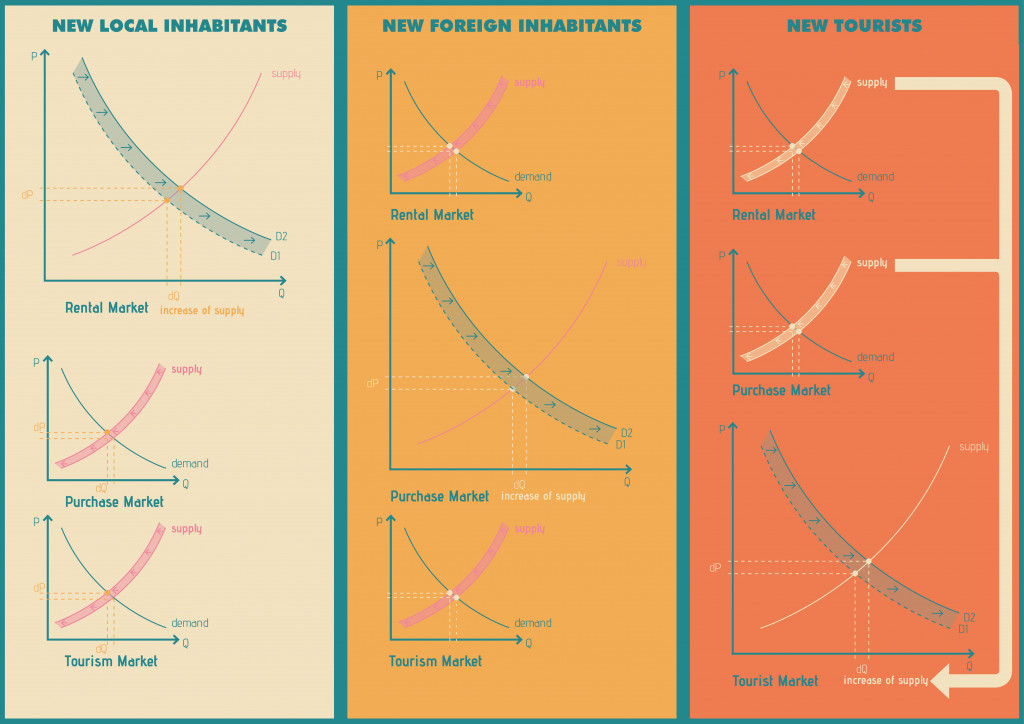

One of main impacts of all types of gentrification is an economic one. Using the economic model of supply and demand it is interesting to note the behaviour of the rental, purchase and touristic markets in relation to one another.

When an area suffers from inner gentrification, a pressure on the rental market appears. This is obviously a simplification, as locals also buy apartments, and therefore pressure is also applied to those markets.

Inner Gentrification

When an area suffers from inner gentrification, a pressure on the rental market appears. This is obviously a simplification, as locals also buy apartments, and therefore pressure is also applied to those markets.When the demand rises on those markets, the market naturally increases the supply to reach the balance point. To increase the supply in a finite market where hardly any new product is produced (or built, in this case) the market will pull the new quantity from other markets. If the rental market requires more flats, it will pull them from the purchase and from the touristic market, as well as other markets (such as the office, and other uses).

Outer Gentrification

In case of outer gentrification, the pressure builds on the purchase market rather than the rental and touristic markets. This exemplified especially in situations where the Spanish government promises the citizenship to any foreigner buying a house in Spain over 500.000€ causing the demand to increase. The market will then pull the required additional product from the rental market, as well as the touristic one.

Touristification

When it comes to touristification, the behaviour of the markets remain similar even though the end results vary from the other. The increase of demand (like the one Barcelona suffered after the Olympics, or the specific one it gets when there is the Sonar Music Festival), is met with a pulling of product from other markets. In the areas where the demand for tourism exceeds all others, the market will pull from other linked markets resulting in the forced or choice evictions of the locals who are not able to afford the fluctuating prices.

One of the common characteristics of these processes is that it creates a displacement of locals but unlike the other two, touristification causes a city to be deserted by its locals as it is overrun by foreigners who don’t contribute to the city.

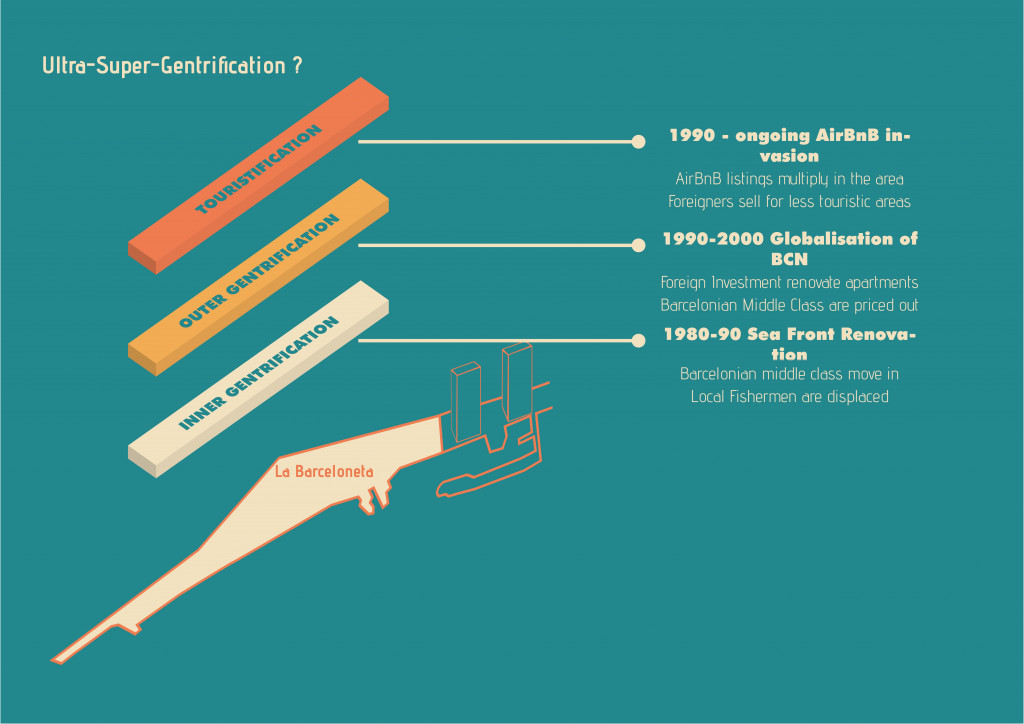

An excellent example of this happening is Barcelona itself. The local citizens which consisted of fishermen and port workers started being displaced by the Barcelonian middle class in the late 80s and 90s. They came from less central, less diverse areas of the city and created a significant difference in the economic status of the city due to their higher incomes. But in the 2000s, Barcelona evolved to be one of the major global cities. Young foreigners with university studies were looking for the diversity of a central dense neighbourhood while being next to the beach. That led to the displacement of the previous gentrifiers.

However, the present condition is even renderring them powerless as increasing tourism leading to the increase in the number of airbnbs and touristic apartments are causing neighbourhoods to be ultra gentrified in addition to losing its original character.It is fair to say that Barceloneta is being ultra-gentri-touristified.

This evolution or overlap of these process are not unique to Barcelona.This is a growing concern in other cities like San Francisco,Amsterdam and Hong Kong, New York etc.

World Policies

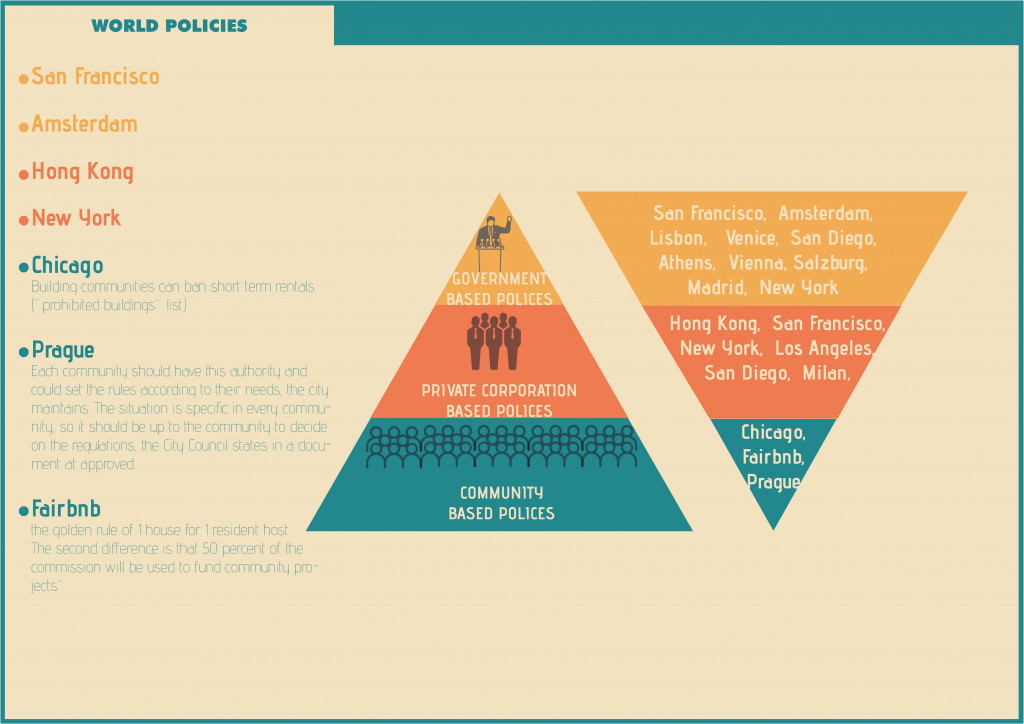

The concern of gentrification has been tackled differently all over the world by using different policies.Upon examining them, they can be classified into three different types of policies based on the stakeholder targeted and enacting the policy.

Government based Policies

These are usually top down policies that involve around declining permits to global brands and excessive touristic apartments that exaggerated the problem.It also involves promoting awareness to the tourists about the repercussion of their actions.

Private Corporation Based Policies

These are policies that are enforced on private organizations that create major impact on the city in order to regulate them.Also, aggressive fining in order to give incentives to regulate their activities without licenses are also part of this policy.

Community Based Policy

These are policies that divulge power to the people to regulate the conditions of their neighbourhood or city.This is an effective means of making a policy that is both participative and dynamic.

In Barcelona, two main policies have been applied, not without controversy.

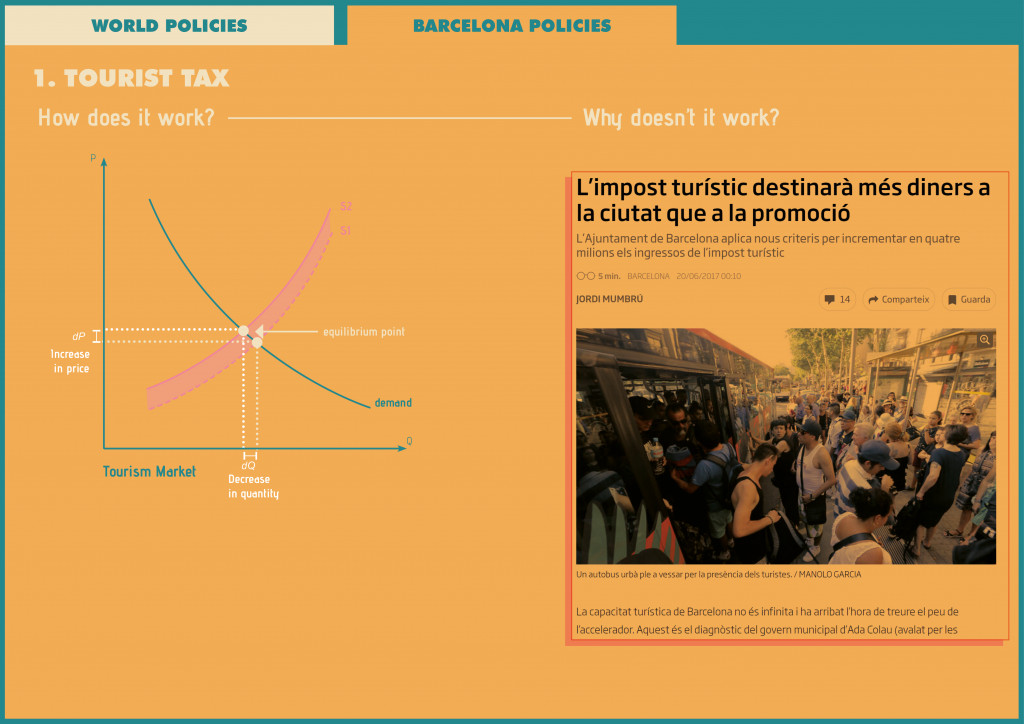

- Tourist tax

The first one was the tourist tax. It is a direct tax on tourists based on the number of nights they are spending in the city and their economic level – only based on the hotel category that they book . They currently only tackle the visitors who are staying in hotels, as they are the ones collecting the tax. This is aimed at de-incentivise tourism, while compensating its externalities.

In theory, taxing is an effective measure. The increase price of the supply brings the supply curve up, reaching a new balance point, that implies a decrease of quantity of tourists and an increase of price.

So, why is it not working?

The money collected from this tax (along with more money from both the Catalan government and the Barcelona Council) is mostly being used to promote the brand Barcelona. Although aimed at a broader goal (bringing foreign businesses in the city) it ultimately promotes Barcelona as a touristic destination, more than fighting the externalities of this practice.

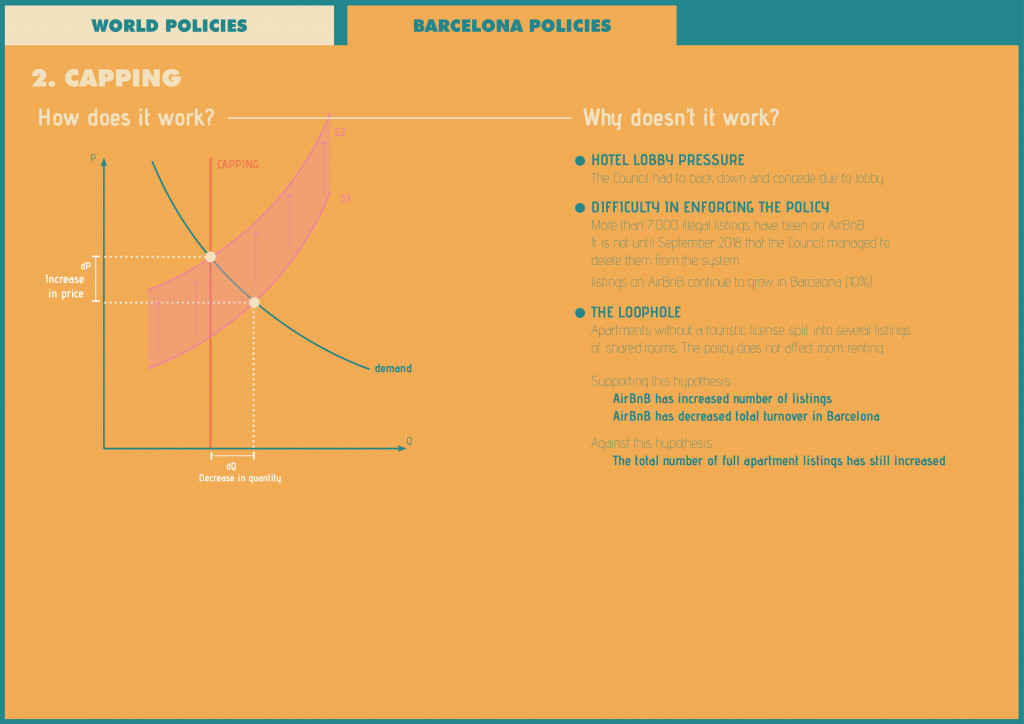

- Capping

The second measure is capping. In 2015 Barcelona’s Mayoress Ada Colau enforced a halt on all hotel licenses in Barcelona, as the administration considered the city had reached (and surpassed) the capacity to receive and absorb tourists. This was not free of controversy, as a cap affects markets in a brutal way.

Since 2015, the Council also stopped conceding more licenses for the use of apartments for touristic accommodation, thus trying to apply this cap in the most growing touristic market, which was AirBnB.

A cap can effectively redraw the supply & demand market, making the balance point move and an amount of apartments be returned to the housing market. This comes naturally at the cost of an increase of price, and a reduction of demand (this demand will then go to competing touristic markets (Valencia, Italy, Croatia, etc).

In Barcelona, again, these effects are not apparent. Why?

- The hotel cap was contested and the Council had to back up and concede on some ongoing licenses.

- On top of plainly illegal listings, the Market exploited a loophole on the touristic apartment cap. Since the policy does not affect room listings, but only full apartments, an apartment listing that does not obtain a license can be split into as many listings as rooms and be invisible to the policy, while still being fully used for touristic purposes.

- This can explain that after the cap on touristic apartments, the total amount of listings on AirBnB kept increasing, while their total turnover decreased.

- The effect of these measures is only visible after a time. With ongoing licenses already approved, more hotels were built in the following two years. A delay of a few years is to be expected before the results become apparent.

T4C

So, how can it be improved.

We do not want (or need) to reinvent the wheel here. We acknowledge the effectiveness of the strategies behind these, and we have explained why those are not visible in Barcelona. In a nutshell, the implementation of applying and approving and declining licenses, with the added issue of the tracking of these activities, is a complex and expensive bureaucratic task that can drown an administration in bureaucracy.

The policy implemented by FairBnb of one host one Flat is a good way around it. With linking real users ID to the listed flat this can be simplified greatly and the rules enforced greatly.

However, there is a second problem. The city has artificially established three (now 4) areas. One where tourists have surpassed the capacity of the area to absorb it. Another one that has reached the limit. And another two areas where tourism can still increase.

This poses a question. What is the magic number? How do you measure the resilience of a neighbourhood and how do you determine the percentage of tourism that surpasses it? The city is a living and changing creature, and its resilience will come from adapting and adjusting to new realities, both through time and space.

The project proposes the adaptation and evolution of these policies (both the tax and the capping so that):

Regarding the cap

- The proposal shifts from a top down approach, where the city council determines the “magic number” to a bottom up one, where citizens of each neighbourhood determine through their feedback the capping level in each neighbourhood and time of the year.

- An evolution is proposed from 4 areas to as many as neighbourhoods

- A change from a static categorisation of areas to a dynamic one is proposed, that can change through time or through the current occupation of tourists in the city.

- The transfer from a license based policy, to an occupation based one in real time, where the possibility to rent a space out will cease as soon as the capacity limit is reached, therefore not favouring lobbies

Regarding the tourist tax

- We evolve from a segmented tax (based on hotel stars) to a fully progressive one, that is both percentual (from the price paid for the accommodation) and progressive (tax increases as the occupation approaches the limit).

- We evolve from a hotel based tax to a wholistic one, with the collaboration of private platforms.

User experience

How will this work?

Carla is a Parisian that wants to stay in Barcelona for a few days. She logs into Airbnb and chooses a room in a shared flat in Barri Gòtic. When clicking, she is announced the area is close to saturation in that period, and she will be taxed a 10% of her price. She also receives the suggestion of the closest not saturated neighbourhoods where the tax will be lower.

Erik is a San Franciscan who will bring his family to Barcelona in February. He is planning to stay in a hotel in Eixample. He uses Booking.com’s website to book it. When doing so, he is informed the area is in low occupation, so he will be charged a 2% of his accommodation price as tourist tax.

If Carla had done this in the 20th of July she might have received a message that the area was fully saturated, and would get suggestions for other areas where to find accommodation.

This system will reward the early birds, making tourism to Barcelona still possible to lower income tourists despite the tax, while collecting a higher tax for each neighbourhood at the same time.

Miquel is a neighbour of Poble Nou. He logs into the tourist tax programme on bcn.cat and with his ID he can access the data on his neighbourhood. He can see the allocation of taxes in his neighbourhood, and submit his changes on specific dates, or for the whole year. He can alter both the segments of the tax, or the maximum limit of tourists per night allowed. His vote will accumulate with others to the collective allocation.

He can then check the occupation of tourism in his neighbourhood throughout the year, and how much tax money has been collected from it. He can also navigate to other neighbourhoods, or check the overall data for the city of Barcelona. Last, he can check what is being done with this money, and vote for projects for his neighbourhood or at the city scale.

Impact

On the one hand, this policy will not only track and regulate the tourist influx in each area of Barcelona, but it will on the one hand help disperse this tourism throughout the different areas of the city, helping to share the load of the externalities and potentially reducing its massification.

On the other, it will empower the people through giving them the tools and responsibility to manage the policy, and what the money is being used for.

A part of the tax (determined by the neighbours) will be feeding a public fund to fight evictions. The rest of the tax collected will be put in the hands of each neighbourhood. They will collectively decide which local projects get executed, in a crowdfunding way. It will build community while raising awareness of the good that tourism does, therefore giving incentives to the community to keep a balanced cap level that allows for these projects to occur while keeping the nuisance and impact of tourism in a level that can be absorbed by the community.

Hopefully, it will change the perception of tourism from the infamous Touristophobia, to a balanced symbiosis between the guests and the hosts.

T4C is a project of IaaC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia

developed at Master in City & Technology in (2018/2019) by:

Students: David Casanovas Tatxé, Raeshma Janardhanan, Xinyu Zhang, Haining Zhou

Faculties: Luis Falcon, Diego Pajarito